What X silencing a journalist reporting on hacked materials shows about the ethics of weaponized disclosures

As always, thank you for subscribing and amplifying Civic Texts, which will not be sustainable without you. Many thanks to everyone who has supported my work, particularly folks who have subscribed to memberships since our soft launch in April.

Please keep sharing these newsletters on social media and forwarding them on email. Organic growth by word of mouth and social recommendations is incredibly helpful. You can always write to me with questions, comments, tips, features, or other feedback at alex@governing.digital or call/text at 410-849-9808.

Good afternoon from rainy Washington, where the remnants of a hurricane are drenching us on their way up the East Coast of North America. Godspeed to the first responders and aid workers helping people in the communities affected by Hurricane Helene’s path.

Today, I have troubling news to share: Agents of a foreign government have used social engineering and technological expertise to hack into a presidential campaign, thereby potentially compromising networks, legal documents and other information held on the accounts and devices of a candidate or advisors. We don’t know if a hostile nation now has confidential legal documents or even classified war plans.

Intelligence operatives are now trying to leak some of these hacked documents to journalists at major media outlets, seeking to sow doubt, division, and discord in an historic election using active measures.

Is this scenario from 2024 — or 2016?

Yesterday, the company formerly known as Twitter suspended Ken Klippenstein, an independent journalist, after he published a dossier that the Trump campaign compiled on Senator J.D. Vance over on his Substack account.

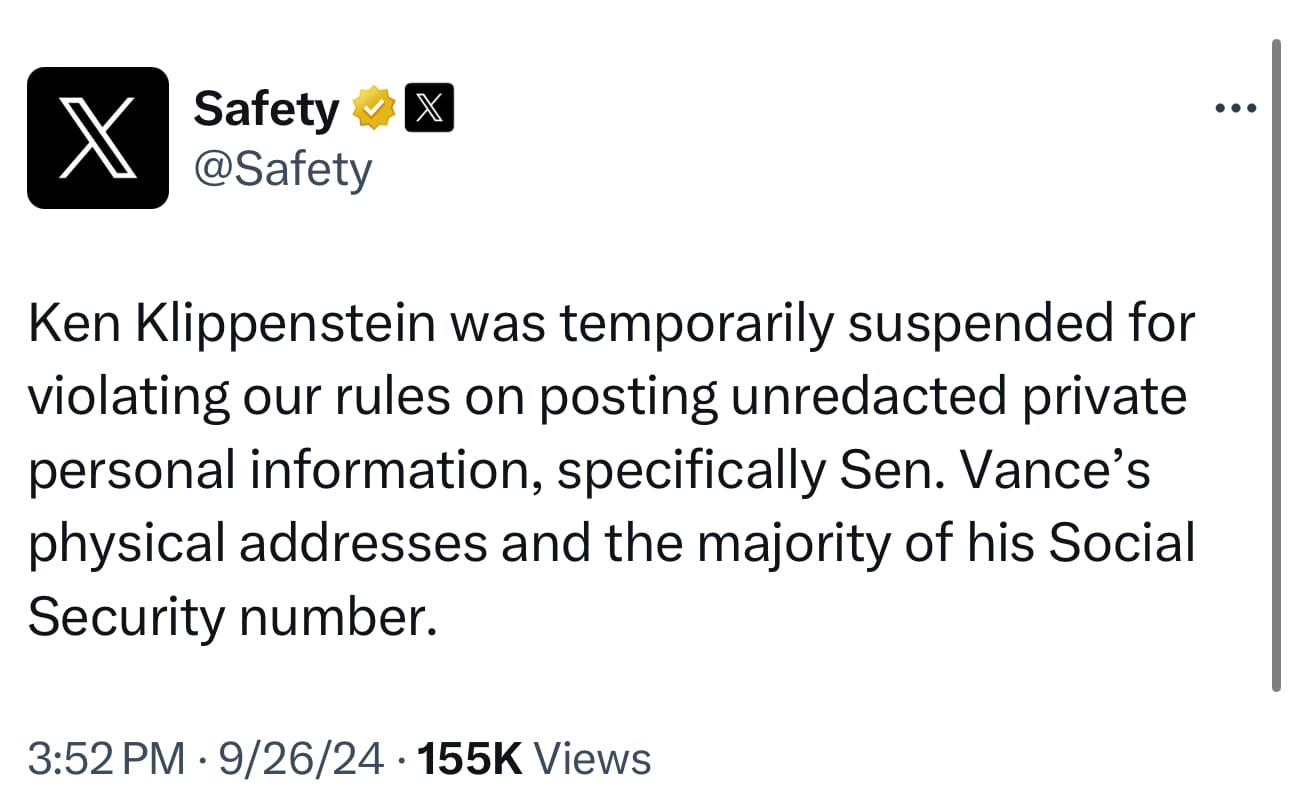

The @Safety account claimed that Klippenstein was “temporarily suspended for violating our rules on posting unredacted private personal information, specifically Senator Vance’s physical addresses and the majority of his Social Security number.”

The Verge reported that X also began blocking the URL to the post on Substack, scrubbing the hyperlink from search, & had deleted their hacked materials policy.

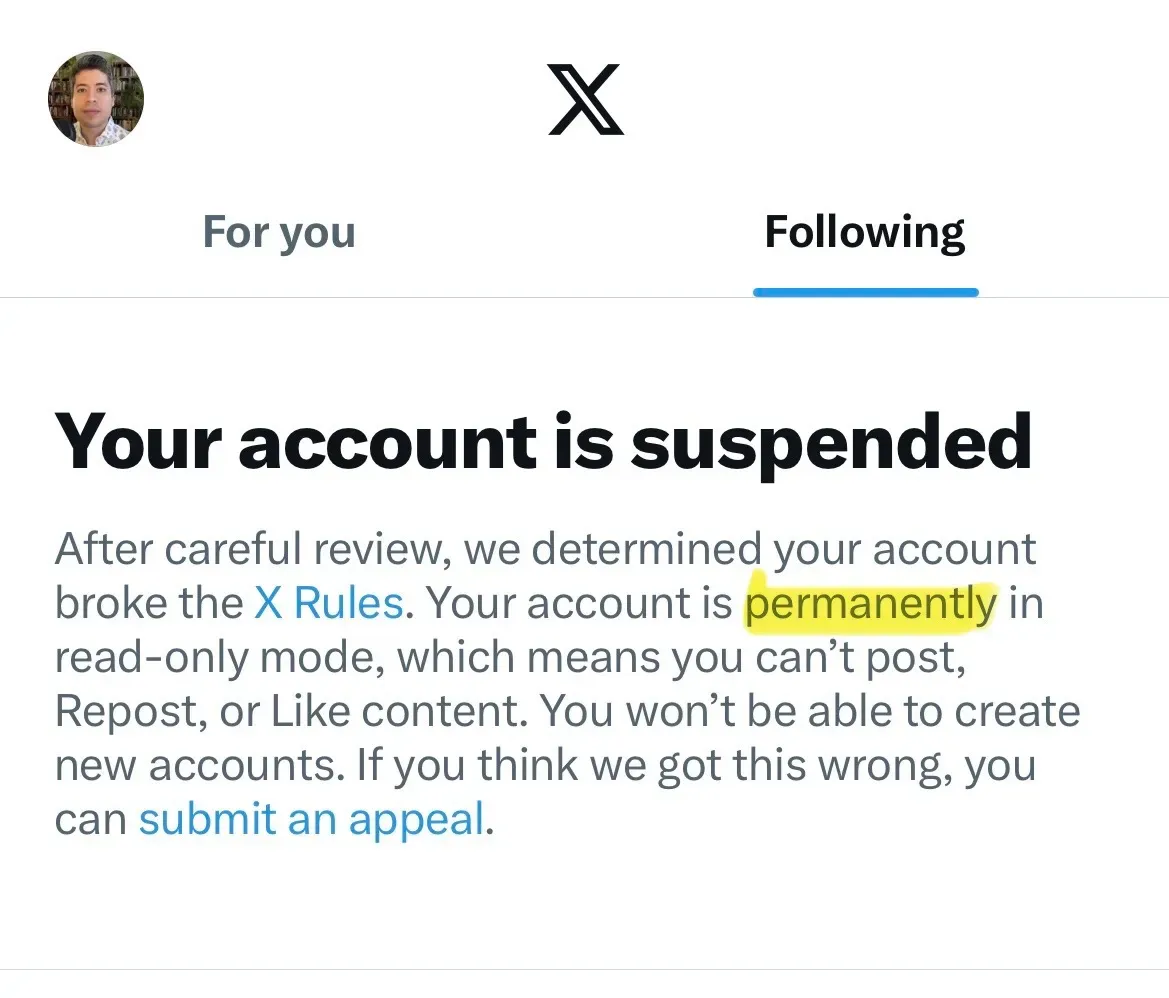

Today, Klippenstein writes that X has told him that his account will be placed in permanent read-only mode after they determined he had violated the company’s rules meaning that he won’t be able to tweet, post, or reply.

He’s describing this as a permanent ban, but it’s more like an endless silencing, like being consigned to a silicon Purgatory without end. It’s parallel to the week-long limitation Meta applied to my Threads account earlier this year after I triggered an automatic filter, but eternal. (It’s not the action of any free speech absolutist, but then that’s never been Elon Musk’s actual position.)

As Klippenstein notes in his post arguing that this silencing by X is political, the company has used a hammer where it could have wielded a scalpel.

X typically provides users who post something in violation of its policies the opportunity to remove the offending posts in order to have their accounts reinstated. I have received no such offer. As an experiment, last night my editor and I decided to redact all “private” information from the Vance Dossier in my story here at Substack. Despite filing an appeal in which I mention this, I remain banned. So it’s not about a violation of X’s policies. What else would you call this but politically motivated?

That conclusion is hard to avoid. Whatever remains of the Trust and Safety department could have required Klippenstein to delete tweets in order to regain access, just as X did in 2022.

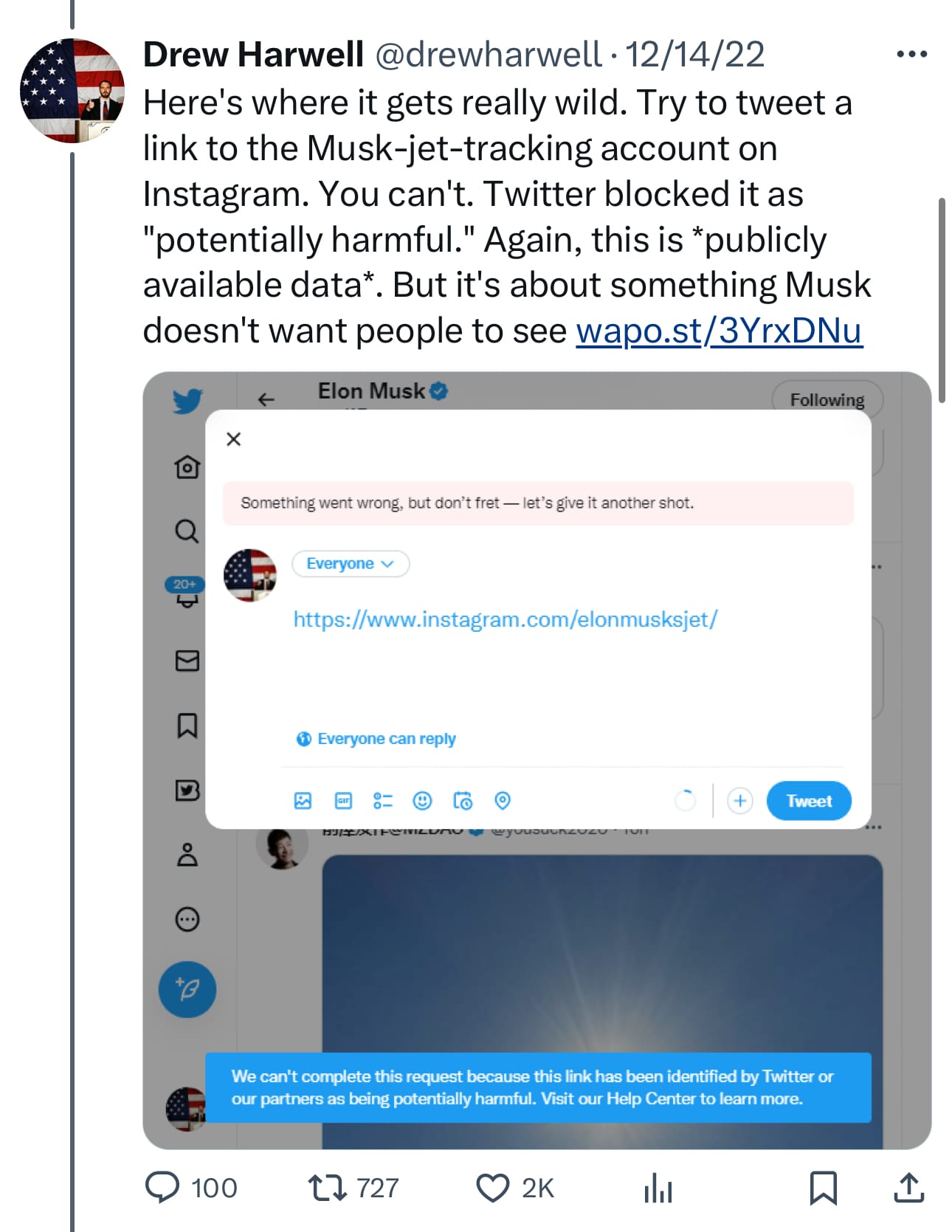

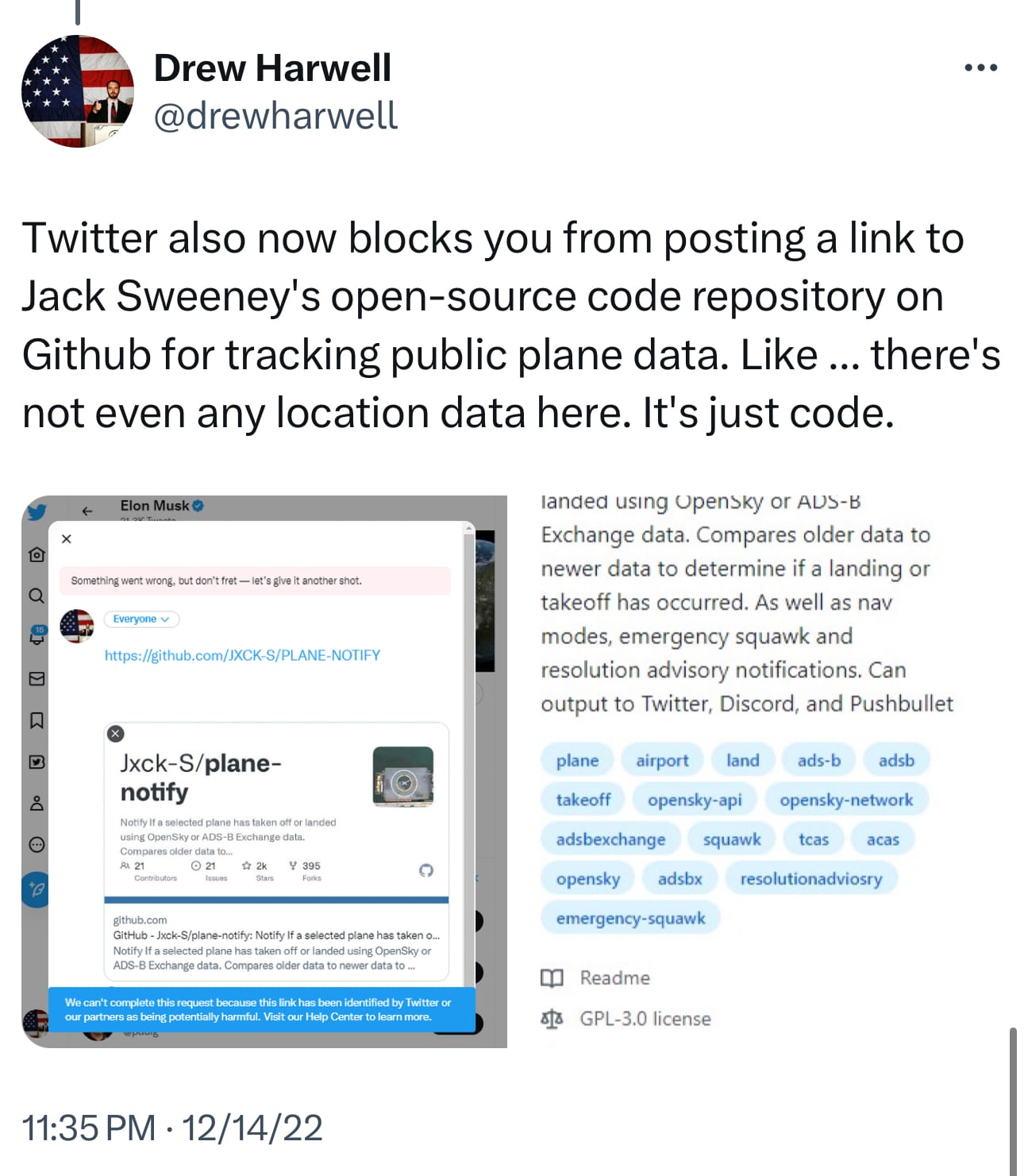

If you have forgotten, Elon Musk decided he didn’t like journalists tweeting about the @ElonJet account and changed the rules to justify suspending accounts and blocking a link.

It appears that Musk’s overt partisanship is now expressing itself in his governance of the platform before an election, unrestrained by whatever remaining staff who might counsel caution about how the platform moderates journalists or “hack and leaking operations in the buildup to a historic election.

But now that he has taken sides, there is an obvious incentive to limit the reach of information he views as damaging to his preferred electoral outcome, despite the risk that doing so will call more attention to it.

Washington Post reporter Drew Harwell’s reporting on the suspensions and filtering from late 2022 shows how the same pattern seems to be playing out again today.

As Harwell noted, using public information to report on public figures is fundamental to investigative journalism, from public records to regulatory filings to data generated by sensors in buoys, transponders in planes and ships, or environmental monitoring stations.

So it’s deja vu, all over again.

As wih the @ElonJet saga in 2022, Klippenstein didn’t tweet a full Social Security number or post a non-public address to doxx a sitting Senator or vice presidential candidate. He linked a page with a link to a document with that has a partial SSN and home addresses.

X seems to have removed the hacked materials policy which would have clarified how the platform will treat accounts like this, which link to other websites or services where leaked, stolen documents or data reside.

The ambiguity and uncertainty left in the wake of this could — and I suspect, will — chill the expression of every news media outlet, academic, nonprofit, and researcher who uses the platform formerly known as Twitter.

As Casey Newton observed at Platformer yesterday, the notion that platforms should carefully govern how people publish personally identifiable information (PII) is sound — especially if there’s a reasonable expectation that posting PII online could lead to offline harm:

“It is bad to incentivize hackers and thieves to steal and post people’s private information, allow it to spread rapidly on your network, and highlight it as a trending topic. Doxxing people can and does put people in danger, and platforms should take steps to stop that, whether the victim is the president’s ne’er-do-well son or the vice presidential nominee.”

Just so.

good platform governance requires consistent adherence to a set of principles, values, and understandable policies that are applied equally to people using a given service. To be charitable, that does not seem to be how Musk and his staff are moderating X, after abandoning any pretense of political neutrality.

That’s why I’ve been advocating for all platforms to adopt the Santa Clara principles for transparency in moderation for many years — and for news media companies to adopt the principles and practices of (open) data journalism.

That means “showing your work” and explaining why and how journalists and newsrooms report on different stories — or do not — to readers, viewers, and other creators of acts of journalism who don’t understand different decision. It does not mean rejecting criticism. Transparency is (still) the new objectivity, in an age when trust in journalists and journalism remains abysmally low.

Almost a decade after John Wonderlich and I warned about the dangers weaponized transparency and selective disclosure posed to public trust in government, I think our guidance holds up. (The bolded emphases are mine.)

Investigative journalists need to review sensitive raw data or original documents to verify facts but do not have to publish them on the Internet. Publishers need to ensure that everyone involved in a story knows when is it ethical to publish stolen data, or data with questionable provenance. As publishing is democratized, anyone with a website or social media account has to think through how to avoid the pitfalls of data journalism in the digital age. The weakest link in a newsroom’s security can expose sensitive data that would change someone’s life forever — or even end it.

Over the longer term, it’s likely that personal or sensitive data will continue to be hacked and released, and often for political purposes. This in turn raises a set of questions that we should all consider, related to all the traditional questions of openness and accountability. Weaponized transparency of private data of people in democratic institutions by unaccountable entities is destructive to our political norms, and to an open, discursive politics.

Indeed, campaign finance information itself, a subject implicated by the hacked emails, faces opposition from those who see any campaign finance regulation as an attack on a free politics. Wikileaks’ indiscriminate disclosure in this case is perhaps the closest we’ve seen in reality to the bogeyman projected by enemies to reform — that transparency is just a Trojan Horse for chilling speech and silencing political enemies.

Traditional publishers operate within the boundaries of traditional restraints, from political norms to funding sources to government licenses for broadcasting on public spectrum. Shifts in technology have now enabled non-traditional platforms to rise that are not bound by any of those norms. As long as we can expect security practices to be unable to prevent such hacks, the vacuum of available remedies makes overreaction from governments too tempting, and invites regulatory over-response.

The threat of future reprisals or censorship by proxies that stifle speech in unaccountable ways, however, is real and relevant to open government everywhere. Overreaction could be well be worse than no reaction. The prospect of restraints on freedom of expression or the press in a networked Fourth Estate without due process is toxic to democracy.

Public debate and disclosure of any potential remedies in Congress is critical, given the way that extra-judicial actions taken by Facebook, Google or payment processors can act to censor publication of data that was properly redacted and informs the public of corruption or criminality. The methods proposed to combat online piracy in legislation proposed in 2011 closely mirror the mechanisms that a public-private partnership between government and technology companies could pursue today, from the DNS system to blacklists on social media. That doesn’t make them wise, but political uproar could reinvigorate their application.

As a society, we’re going to need to decide what governments, financial institutions, and technology companies should be empowered to do, and what constraints they should face in the face of massive hacks and subsequent online disclosures. The history of U.S. government censorship of websites for copyright violations does not give us confidence that an appropriate balance will be struck.

What we can say with certainty today is that in the wake of this series of intentional privacy violations, whistleblowers [and] “white hat” hackers should consider who they’re leaking to, and why. Private data gives people great power, which in turn carries with it great responsibility. In every case, for every person described in the data, there’s a public interest balancing test that includes foreseeable harms. Every person who is entrusted with collecting, protecting or reporting on data needs to think through how open public records should be and to whom, with what friction, in a more transparent age.

We are now living through that transparent age, in the lead up to a historic election with high stakes. This isn’t just a tempest in a teapot: worse is likely ahead in October.

Notably, Klippenstein went back and redacted the PII from the Vance dossier and uploaded it again, to test if X would change its decision to silence his reporting on that platform.

They have not, so far, which validates his decision to build a direct relationshop with people over email, as I’m trying to do with you myself.

Thank you, as always, for listening and subscribing.