What Utah can tell us about the present and future of open government data in the USA

Good morning from sunny Washington, where I’m dealing with watery fallout from the deluge over the weekend. Alex Howard here, with another civic text.

Many thanks to the new subscribers who have tuned in and to the folks who’ve invested in a membership. If you can afford it, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription and help me make this a sustainable publication. You can always reach me at alex@governing.digital with questions, comments, tips, or other feedback.

Today, I’m thinking about public access to information, again.

The arc of progress towards government transparency and accountability can be bent backwards by officials and civil servants who don’t understand open data — or value open government.

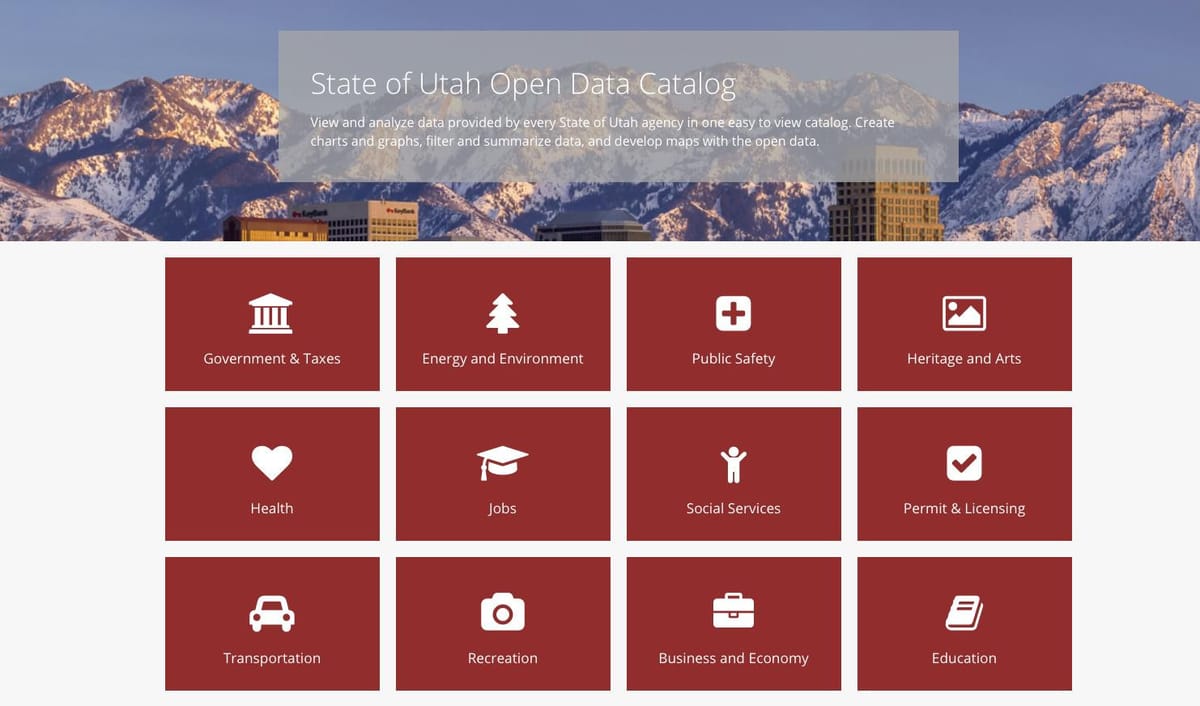

Unfortunately, Utah is now a case study for regression, after the state's chief technology fired chief data officer Drew Mingl for refusing to take down federal data from the state's open data website, & then resigned.

As Mingl said on LinkedIn, public data should remain open to the public! The Utah Investigative Journalism Project, which reported out this story in partnership with KSL.com, made a small error when they described a transparency rule for hospital prices as a law.

Utah’s former CTO made a grave error when he told Mingl to take down a dashboard that actually made that data useful to Utah residents.

Even worse, it appears that Utah technology leadership profoundly misunderstood how to understand the value of opening government information:

In December, the auditors reported to Williamson that the Open Data Catalog datasets had only 45,697 views and 849 dataset downloads. According to the auditors, that meant the expense of the portal over the past nine years amounted to a cost of $43.62 per view or $2,347.70 per download.

Williamson called the metrics "pretty disgusting numbers."

Mingl — who is limited in what he can speak about regarding his former employment — did, however, note those metrics were not representative of the whole site. He pointed to official presentations to the Utah Transperency Board in 2018 that showed that by that time alone, the portal had received over 9 million page views.

Utah Division of Technology Services spokesperson Stephanie Weteling said site metrics from the internal audit were accurate and verified. "We have not been able to verify the numbers that (Mingl) provided in 2018," Weteling said.

In 2024, any agency CTO, CIO, or CDO who seeks to measure the value of an open data platform by page views or downloads — like other “content” posted online — is demonstrating they don’t understand how, when, and why the people they serve benefit from disclosures – or how agencies, officials, and civil servants benefit from the process of cleaning, structuring, and publishing public information.

Gartner analyst Andrea Di Maio highlighted the government-wide benefits of increased internal access to opened data in agencies over a decade ago – and his insight holds up. As Mike Flowers told me, building a data warehouse saved lives and taxpayer dollars in New York City.

Instead, officials, politicians, press, and taxpayers should be measuring the return on investment from funding open data platforms, programs, and personnel by the social, economic, or scientific impact derived from improved internal access and uses AND external uses and re-uses by third parties.

The latter include infomediaries like search engines, consumer marketplaces, and other products and services that ingest structured government data and mill it into applied insights, like business intelligence, predictive risk for fraud, or the quality of nursing homes and dialysis centers.

In 2024, I wonder how many Americans visit Data.gov or "data.state.gov" on a monthly basis. (In an ideal world, we’d see states making that traffic transparent, forking analytics.USA.gov.)

I bet that Utahns don’t turn to Utah.gov/data daily; instead, they engage in discovery elsewhere online, which puts a premium on ensuring that data finds people where we are, instead of hoping people will find data.

A decade ago, I saw state, local, and federal officials encouraging use and re-use of open government data, including documenting impact from releases and engaging stakeholders across American society.

Without renewed commitment to open government and leadership at every level of government, I fear we’ll see more regression, especially if politicians and civil servants don’t understand or use metrics for these efforts beyond server costs or traffic data. “Data winter“ could be coming.