Regular press conferences and town halls make democracy stronger. Every candidate and president should host them.

Good afternoon from Capitol Hill. Alex Howard here, with a second civic text in a given day. What can I say: sometimes, history moments merit attention.

Thanks for everyone who has just subscribed, particularly folks who have supported me doing this work with a membership. Please share these newsletters with your networks, if you think they’re worthy!

Changes on social media mean that organic growth is the only viable way to build a sustainable community, and that only happens if I consistently deliver valuable information, insight, and utility. Please keep your comments, questions, and tips coming at alex@governing.digital.

Today, I want to share some thoughts about much-needed changes that would address the abysmally low regard that Americans currently hold for the national press corps and the state of press conferences, building on a thread I began in 2021.

One of the qualities I’ve aspired to over as a nonpartisan advocate for good governance over the past decade has been fairness and consistency. If an official or politician is departing from democratic norms or undermining the rule of law, I’d call it out, “without fear or favor.” That outspoken approach didn’t win me friends in administrations or Congresses, but I earned a little respect along the way.

I start with first principles: how should a healthy government, party, or governance process work?

In my view, regular press conferences are an essential expression of the transparency and accountability that arm citizens with the information essential to self-governance in a democracy.

Regular press conferences by every President are crucial for modeling transparency & accountability to other world leaders; remember President Obama created a forum where Raul Castro had to take questions?

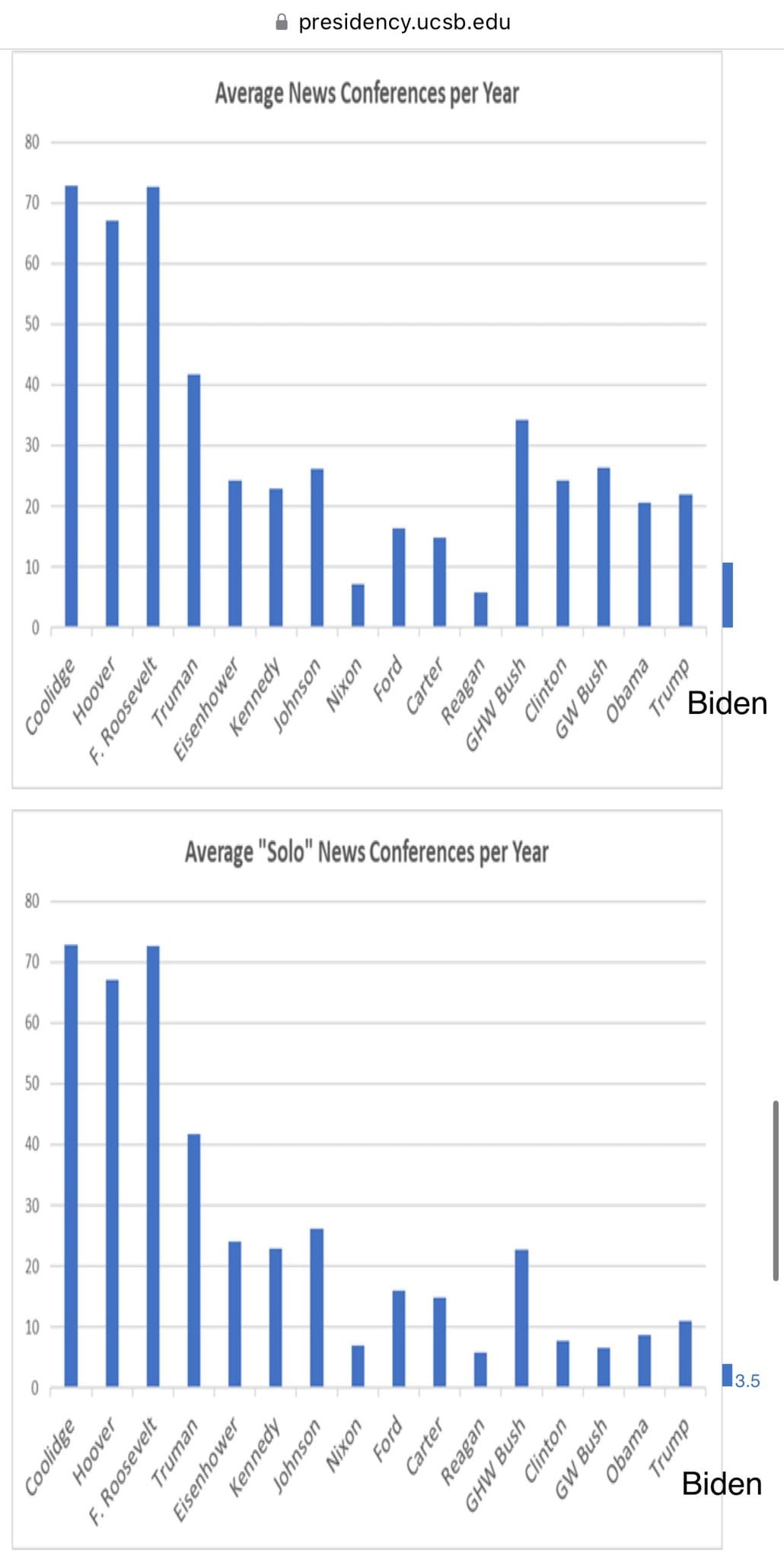

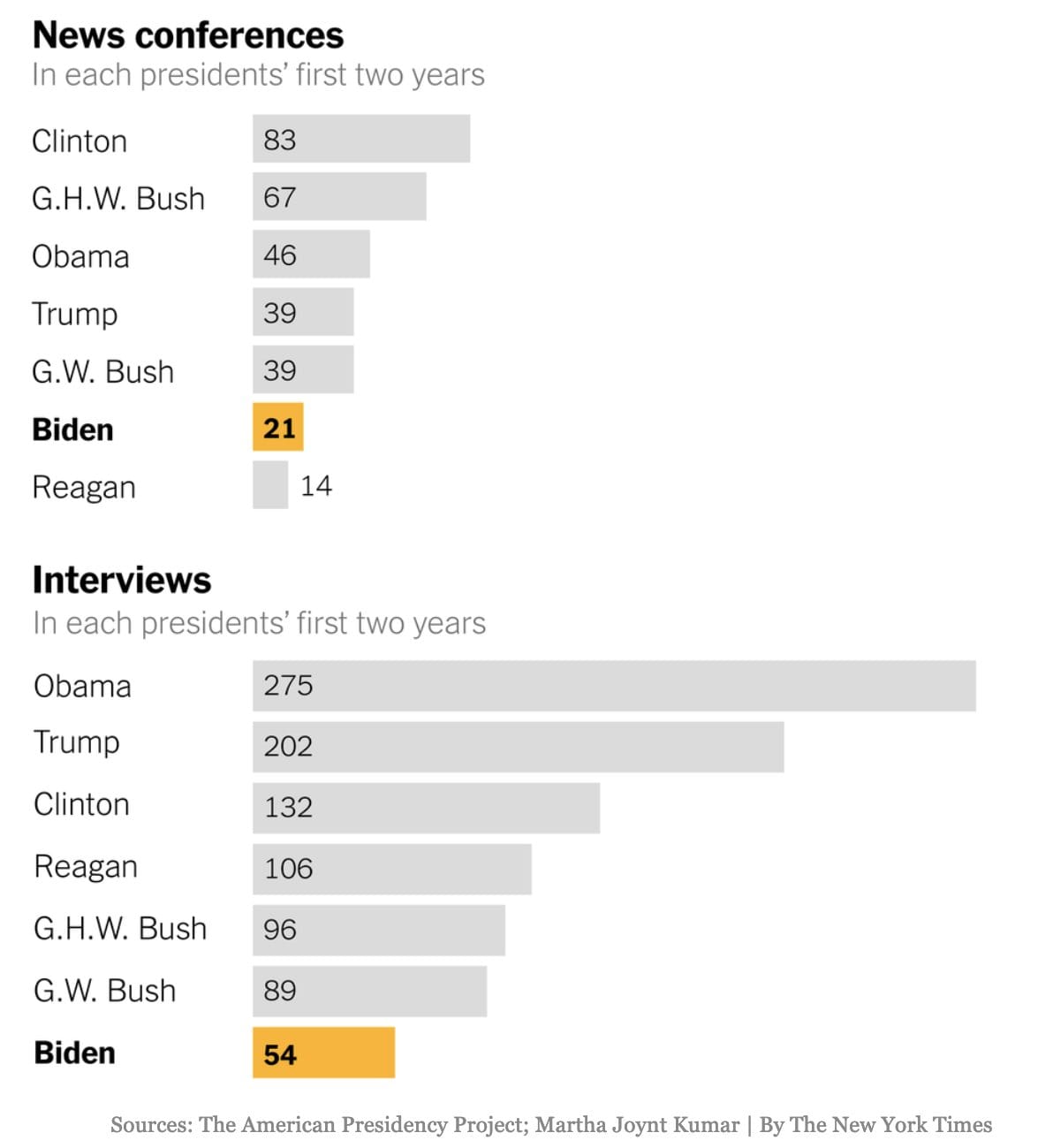

Unfortunately, President Biden did not uphold that norm and discharge that obligation, as data tracked by the American Presidency Project at the University of California at Santa Barbara shows.

President Biden held the fewest press conferences since Reagan, and he did not replace those pressers with town halls or interviews. Instead, he spoke with “influencers” more.

He didn’t host joint press conferences with the leaders of democratic allies in Mexico, Canada, or New Zealand, much less autocrating nations. In doing so, he broke from historic precedent, instead of resetting badly broken relationships and traditions damaged by his predecessors, & then rebuilding new ones.

That is not the sole fault of correspondents grandstanding for the cameras and asking lame questions: President Biden is accountable.

The behavior of members of media on camera is irrelevant to the obligation of every President to hold them, modeling the behavior that each member of their cabinet should embrace.

Proving fitness to govern through open governance prevents information voids from forming that mitigate the risk of foreign and domestic enemies of the Contitution exploiting them with lies and misinformation.

After years of opacity, President Biden passed the baton to Vice President Harris, a decision that came later than it should have in a historic presidency, but reflects the patriotism of a proud public servant who put country over his own personal interest.

Harris, now the official nominee of the Democratic Party, is now facing bad faith criticism from her political opponents for not holding a press conference since Biden withdrew from the race, alongside good faith criticism from media watchdogs like Margaret Sullivan.

I hope you’ll count me among the latter.

When you hear Harris’ political opponents clamoring for a press conference, remember how few of them spoke up in 2019 and 2020, when the Trump White House didn’t hold press briefings for more than 300 days — much less rebuke the former President for calling journalists “enemies of the people,” echoing Mao and Stalin.

As I told Business Insider in 2016, regular press conferences are an essential part of the accountability we expect of every President & all of the presidential candidates who aspire to the highest office in the country — whether their last name is Bush, Obama, Clinton, Biden, Kennedy, or Trump.

Sitting down for interviews, holding off-the-record conversations with correspondents, or speaking with “influencers” can inform voters about a candidate's views, but none are a replacement. It might be good politics to skip them, but it’s not good governance.

As Washington Post columnist Perry Bacon Jr. wrote last week, “Harris is making a mistake.”

She should be doing interviews and other engagements with journalists, in recognition of their important role in democracy. In particular, she should speak to journalists who specialize in policy reporting.”

A presidential campaign is a national conversation about the state of the country. The candidate giving the same speech over & over again is a monologue, not a conversation. Harris isn’t taking questions from voters at her events on the campaign trail or in other forums either.

I’m frustrated that the main anti-Trump candidate has started her candidacy by breaking with the democratic values of treating the press as an important institution and answering questions from reporters and the public.

I agree with most of what Bacon wrote.

As he sharply observed, Harris hasn’t been taking questions from voters in town halls, either, online or off. Talking more with the press and public would show how she’d govern.

The American press has always been a circus. That doesn’t change why candidates, officials, and elected leaders hold press conferences and sit for interviews.

Poor behavior by members of the press corps has never freed governors, mayors, or presidents from their responsibility to inform and be accountable to thone they serve.

The Trump years, however, made the dynamic in Washington far worse. He intentionally created bedlam with “chopper talks” where reporters had to shout & he could pick and choose which questions to acknowledge or answer.

But before he corrupted the form and co-opted the format, regular press conferences, town halls and interviews have been part of the hard work of campaigning and governing in the United States for decades — for good reason. They show our leaders are not above the people, but accountable to us.

At their best, they make candidates stronger and demonstrated whether they understand policy, history, or the complexities of the governments they seek to lead.

We’ve all seen them at their worst, too — and if you haven’t seen Americans be witheringly critical about the quality of questions that candidates and presidents get, you’re not paying attention.

What’s missing is creative thinking on both sides of the microphone. On the government side, I’d like to see officials and politicians across the country test two innovations, now and in January 2025:

- More participatory democracy. Hold monthly press conferences. Host quarterly town halls for people to co-create public knowledge in person. Create weekly online chats that combine livestreams with crowdsourced questions. Consider them a baseline for a healthier democratic discourse 2025. Lean into hard questions.

- A “public chair” to ask a question directly from the American people, posed by a different credentialed reporter each week. (I first pitched this idea explicitly to the White House in February 2021. (Press Secretary Jen Psaki didn’t reply.) Ask the public to draft questions, and then vote for the questions we most want to be asked. Call it a “citizen’s agenda,” riffing on professor Jay Rosen’s concept for news media outlets. If the White House Press Secretary commits to answering the top question, it will create an incentive for people to participate.

On the press side, it seems clear there’s a collective action problem in the national press corps that’s weakened their influence. This shift was epitomized by the Trump White House ending regular press briefings, without recourse, and ”going direct” on social media, where the president was his own communications director.

Trump has since made a mockery of interviews and press conferences in which he employs the “gish gallop,” flooding the zone with a tsunami of fabulism, falsehoods, and flailing projections that overwhelm the capacity of journalists to fact-check not only in real-time, but after.

This is an autocrat’s play. Politicians press needs fresh thinking to counteract it and move forward with formats that serve the public, instead of turning us off.

While press associations can and do advocate for better access and safety for their members, we haven’t seen much progress on pushing back on opacity by default created by “on background” conditions nor the innovation in press conferences to hold leaders accountable for governance and policy decisions.

The press corps needs to begin cooperating better to change this dynamic, starting with asking a question again if a politician or official didn’t answer it. Sunday morning news show hosts should refuse to “move on” or “leave it there.”

I bet that tougher questioning of politicians seeking to evade accountability will not only better inform publics, but create fresh interest in members of the press who explain why and how they’re trying to improve interviews and press conferences, with explicit dialogue around why news media have lost trust and are seeking to rebuild it.

I know it may be deeply unfashionable to be earnest about the role of the press in government and politics in a moment when people are justly angry at the manifest flaws across the media ecosystem of the United States. Bacon is right about the issues in our political press corps, too.

There is no singular or monolithic “Media” in our country. There is a heterogeneous mix of papers, magazines, broadcast TV, cable, radio, satellite, and digital news outlets, + state agencies, with a huge range of ethics, editorial standards, and ideological views, & now “pink slime” partisan sites.

I still believe that journalists are the immune system of democracy. When governments of the people embrace journalism as a public good that produces the information required for publics to be self-governing, the incentives to protect, defend, and preserve news media become clearer.

So are the incentives for autocrats to demean, discreet, and delegitimize the press as partisans, liars, enemies, and spies.

I believe regular dialogue with the press and public in participatory forums over time has immense upside for building and retaining trust and resetting eroded democratic norms if elected leaders and officials are willing to tolerate more risk.

That could be a way forward to a healthier politics, if we can make and defend civic spaces for it.