Telecom companies should disclose online archives of campaign texts

Good afternoon from Washington, where fall is in full swing and election day is just over two weeks away. I took some time offline this weekend to build up resilience for what lies ahead. I hope you did, too.

Many thanks to everyone who has subscribed to Civic Texts since my last dispatch – particularly paid memberships! – and all of the direct support as I continue to work on what's next. It's meaningful to me my family.

Many thanks to everyone who wrote in and shared what's in your civic information diets! You recommended Memeorandum, Civil Discourse, Your Local Epidemiologist, Thinking About…, Breaking the News, The Best of Journalism, All Sides, DemocracyDocket, and Letters from an American. My favorite might be the subscriber who reads the Congressional Record every day!

Please keep those email newsletter suggestions coming at alex@governing.digital – and send photos of what 21st century infrastructure looks like in your community, too, if you feel so inspired.

New phone, which campaign is this?

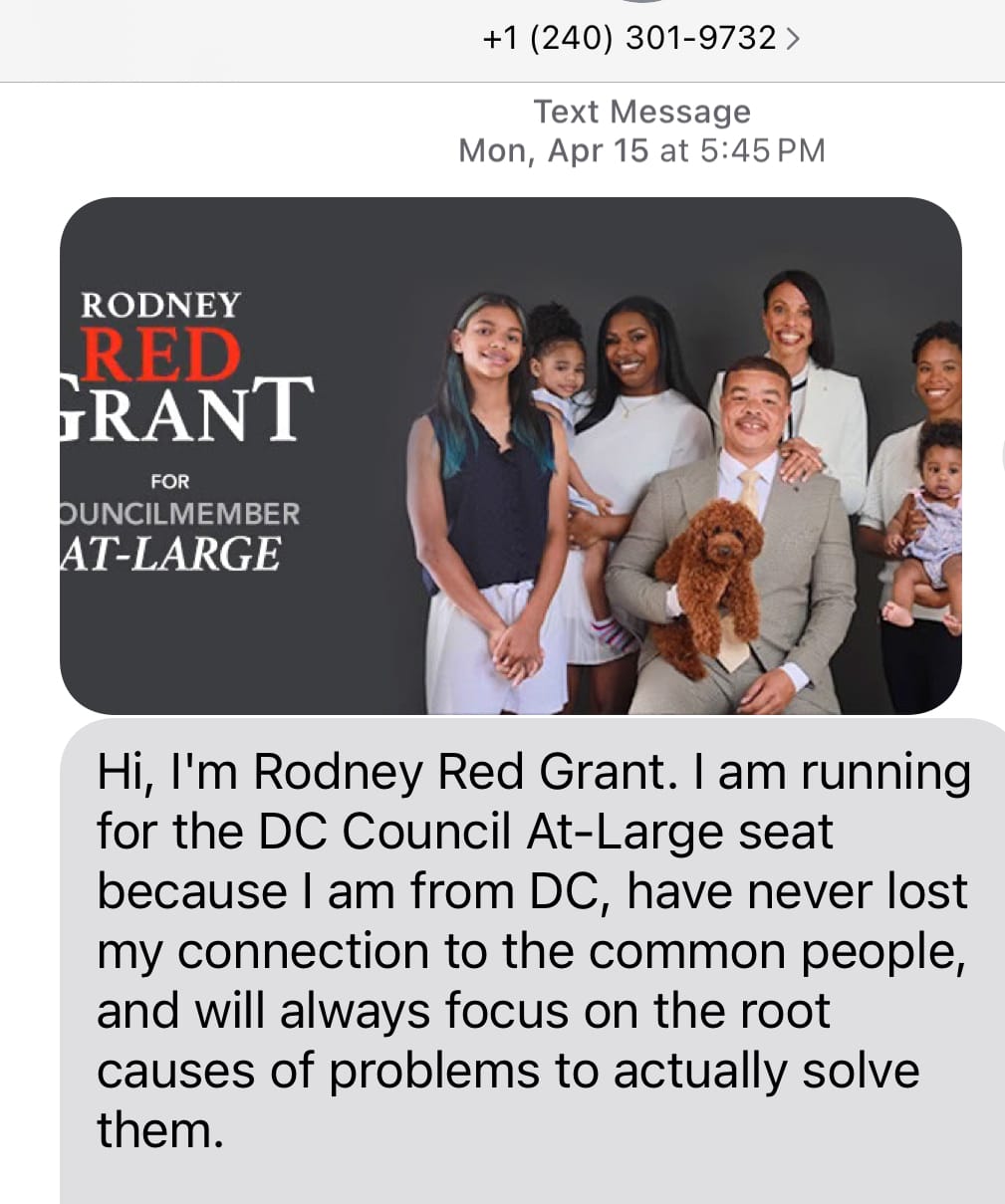

I don't know about you, but I've been getting a bunch of unsolicited text messages from local and national politicians.

As a result of those texts and a signal from a reporter, I'm thinking more about a specific kind of civic infrastructure that's mighty relevant during election season and in their wake: political ad files.

For those unfamiliar, those are the records of paid electioneering – aka those campaign ads that are all over the place in many states right now. For many decades, broadcasters have been legally obligated to maintain these ad files at stations for public inspection.

It took a concerted legal effort from a group of campaign finance watchdogs to get those files online, however, instead of locked up in a cabinet that reporters had to go down and page through, like the card catalogs and stacks my fellow travelers from the 20th century remember at libraries.

As a result of those efforts, the Federal Communications Commission finally approved rules in 2016 that required TV stations and radio stations to publish their political advertising files online.

In 2024, the public, press, politicians, and watchdogs can all go to fcc.gov/publicfiles to access to the “public inspection file” for "licensed full-service radio and television broadcast stations, Class A television stations, cable television systems, direct broadcast satellite providers, and satellite radio licensees."

But more than seven years after we called on technology companies to publish political advertising files online, there's still no public inspection file at FEC.gov for the corporations that operate social media platforms, nor regulations requiring them to do so.

The reasons aren't particularly subtle: Facebook lobbied against the bill, and former Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell is not a fan of campaign finance reform and transparency for donors. Both he and and the current Senate Majority Leader, Chuck Schumer, have refused to give the Honest Ads Act a vote on the Senate floor, despite the growing need to add transparency and accountability to online political ads,

As a result, the Facebook Election Commission, X, Google, Snapchat, and other corporations continue to show the limits of self-regulation. While the Federal Election Commission did adopt new rules of Internet communications last December which means disclosures and disclaimers are supposed to be displayed on online political ads, there's still no federal legislative mandate that requires technology companies to host an online political ad archive – much less to disclose granular targeting data about who got shown what ad, where, when, and wny.

I had a sense of deja vu about this, all over again, over the weekend when a journalist reached out about a pro-Trump dark money network that was operating a fake pro-Harris campaign scheme. The folks behind “Progress 2028” are applying over $100 million dollars to try to influence the votes of Americans.

Back in 2017, I'd told a Buzzfeed reporter that "highly targeted online ads now present a significant vulnerability for liberal democracies, especially since they are not covered by the comparatively strong legal oversight and public visibility that traditional radio, TV, and print ads are."

That conversation and then the resulting draft legislation and advocacy around it eventually led to the ad archives many tech companies voluntarily maintain today.

I take some professional satisfaction in the fact that the text of the bill I collaborated with Congressional staff to draft was not only adapted but enacted in my native state: In 2018, the New York State Board of Elections rolled out new regulations that created public files for paid internet or digital ads bought by political committees and independent expenditure committees. (§ 6200.11).

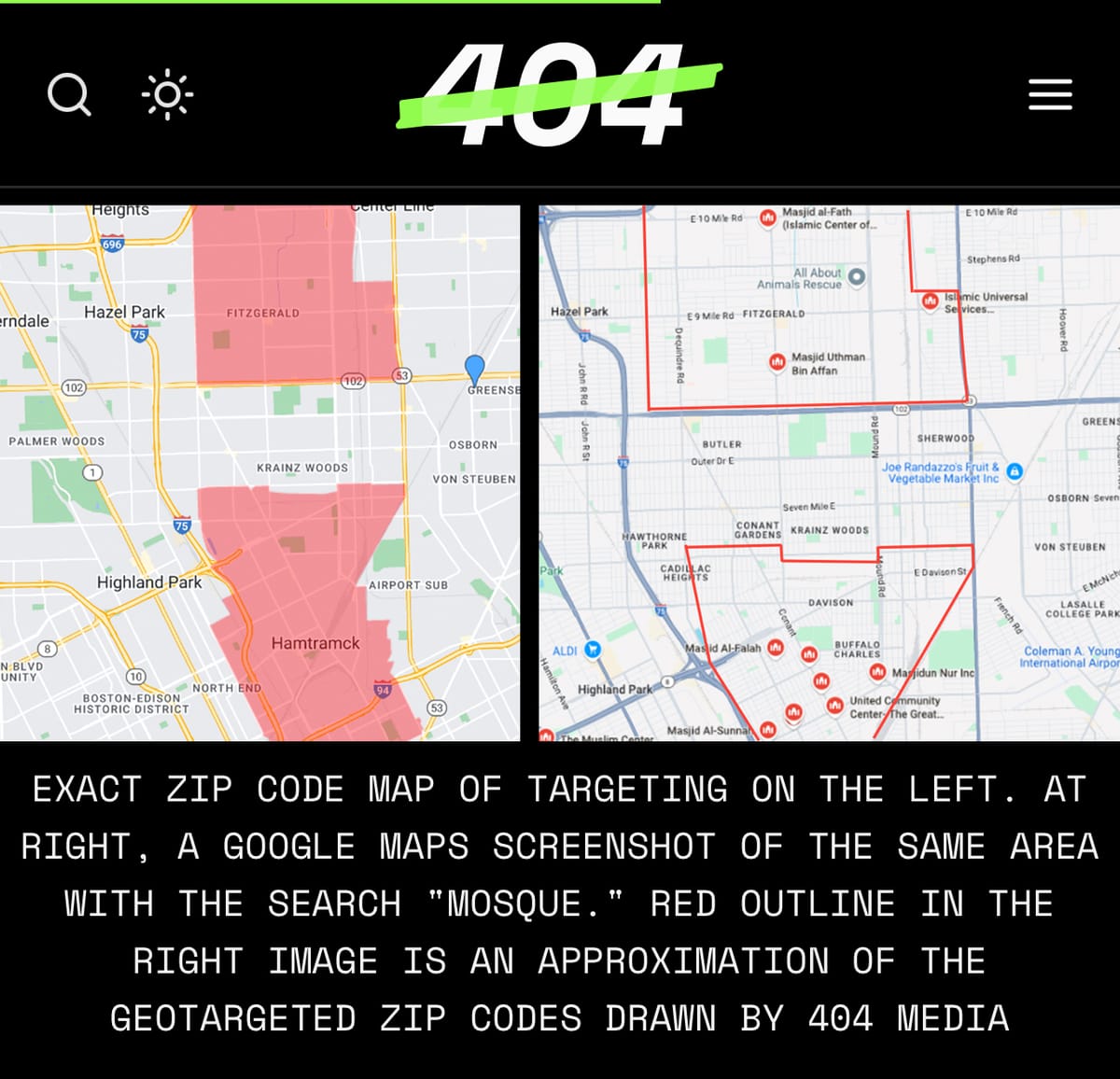

The ad archives that Snapchat (voluntarily!) continues to maintain for public inspection are what enabled Jason Koebler to report on exactly how this Elon Musk-funded poltical action commiteee is microtargeting Muslims and Jews “with diametrically opposed political advertisements about Kamala Harris.”

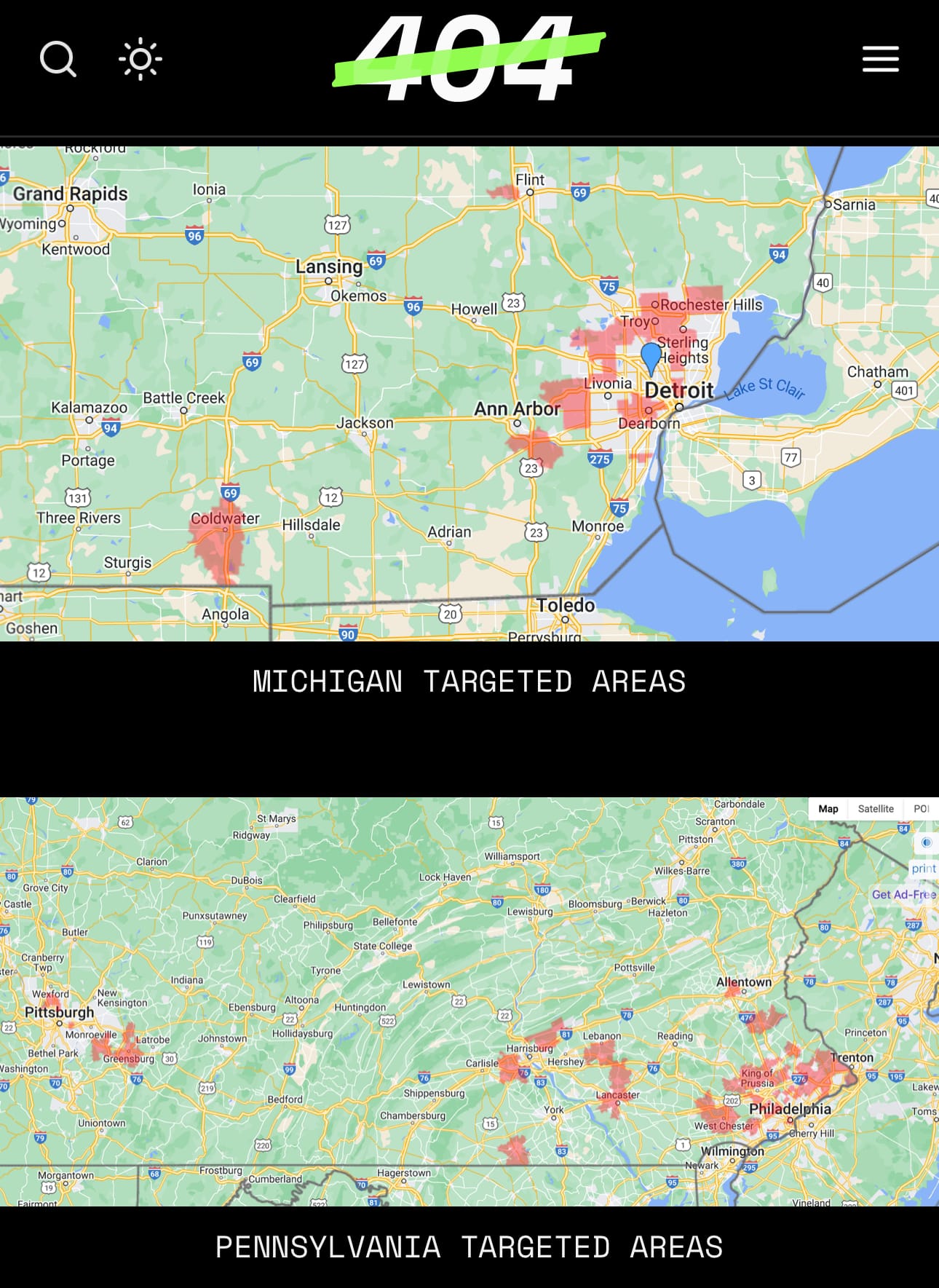

In areas of Michigan with relatively large Muslim populations, the Super PAC is painting Harris as a close friend of Israel and is suggesting that she is beholden to the beliefs of her Jewish husband Doug Emhoff; in parts of Pennsylvania with relatively large Jewish populations, the advertisements call Harris antisemitic and say she “support[s] denying Israel the weapons needed to defeat the Hamas terrorists who massacred thousands.”

To Koebler’s credit, he explained how he was able to do this reporting: opened data!

This investigation was possible because Snapchat makes highly specific political ad targeting available to the public as a spreadsheet. 404 Media downloaded this spreadsheet of thousands of political ads and filtered them to ads targeted by a company called MNI Targeted Media, which notes on its website that “data-driven strategies are revolutionizing political communication.” The Snapchat data shows MNI Interactive has been placing ads on behalf of various pro-Trump PACs, including Future Coalition PAC and Duty to America PAC. We then filtered the spreadsheet to ads placed on the behalf of Future Coalition PAC, which showed a total of 40 different ads that have been collectively viewed 3 million times on Snapchat alone. Twelve of these ads were targeted to 51 specific ZIP codes in Pennsylvania, and 28 of them were targeted to 45 specific ZIP codes in Michigan.

This is lovely data journalism that documents an ugly political story that would not have been possible years ago.

In 2018, I was been worried that we’d see ephmeral social media messages funded by dark money that targeted certain voters and disappeared with no trace. Snapchat upholding one of its democratic obligations made that harder to do on its platform.

In 2024, I assess that highly targeted text messages present a similar vulnerability, with a parallel disclosure cliff that's leaving Americans in the dark.

Telecom companies like Verizon, T-Mobile, and AT&T should begin voluntarily disclosing open ad files of political texts with targeting data — and legislators and regulators should ensure it’s not optional for them or tech companies in the years ahead.

(I doubt Meta or X will ever disclose granular targeting data for political and issue ads without regulation and energetic enforcement that will enable us to figure out who’s being shown to whom and where.)

The advent of geotargeting for humans moving in an embodied Internet will create novel scenarios around polling places and rallies that will make clear rules and disclosures relevant for decades to come.

Why, Georgia, why?

12 years ago, I interviewed my first sitting head of government when I was down in Brasilia, Brazil. Thanks to YouTube, you can watch my conversation about open government with Georgia's Prime Minister Nika Gilauri at the first global summit of the Open Government Partnership (OGP).

While I still have that linen suit, Georgia's commitment to government transparency and accountability haven't held up.

Last week, the Open Government Partnership suspended Georgia "temporarily" until the country withdraws "current or proposed legislation that discriminates, stigmatizes, or hinders the freedom of expression and association of civil society organizations, media representatives and vulnerable groups" and safeguards "freedoms of expression and assembly, the space for civil society and their ability to operate without physical and verbal attacks, including in election periods."

I'm doubtful that's going to happen, which is a loss for Georgians but I win for the global legitimacy of membership in OGP. On that count, as subscribers know, the Open Government Partnership has failed to have a positive impact in the United States since former President Barack Obama co-founded the global multi-stakeholder initiative in the fall of 2011 for a variety of reasons.

Should former President Donald Trump win re-election in November, I expect the United States to be placed back under review and temporarily suspended by the end of 2025.

In my view, the U.S. government should have remained under review since 2019, when increasingly overt acts of corruption, deception and maladministration made a mockery of our continued participation, but for undisclosed reasons the OGP Secretariat and Steering Committee has continued to accept "behavior contrary to process" from a nation whose national security state and police force generally remains addicted to secrecy and obfuscation, not transparency and accountability.

For more on the history of U.S. involvement, read my response to the United States government’s request for comments on its mid-term self-assessment of the United States fifth National Open Government National Action Plan, which was posted on June 17 and can be downloaded as a PDF from Regulations.gov.

It's plausible that the next administration will understand why the U.S. approach to open government has been flailing and take bold action needed to right the ship of state, but I'm not feeling optimistic today.

RIP, Helen.

On that count, I’m mourning the loss of Helen Darbishire, who passed away last Friday. Helen was an extraordinary champion for public access to information in Spain, Europe, and beyond.

The world lost a champion for open government who lit up rooms with her grace, wit, and humor. I last saw her at the European Parliament, before the pandemic. I wish we’d reconnected since. My condolences to her family & all who knew her. We will hold her in the light.

As always, thank you for subscribing and amplifying Civic Texts, which will not be sustainable without you. Many thanks to everyone who has supported my work and thus my family, particularly the folks who have subscribed to memberships since our soft launch in April. Your vote of confidence means the world to me.

Please keep sharing these newsletters on social media and forwarding them on email. Organic growth by word of mouth and social recommendations is incredibly helpful, especially given how hard it is to get attention and conversions on today's "pay to play" digital platforms. You can always write to me with questions, comments, tips, features, or other feedback at alex@governing.digital or call/text at 410-849-9808.