End the “digital dualism” in 2024: What we do and say online is part of real life.

Good afternoon from Capitol Hill, where I’ve been dodging mosquitoes and getting my head around having a sixth grader. Alex here, with another civic text.

Thanks to everyone who has signed up since my last dispatch, particularly the paid subscribers who have supported this work. If you can, I hope you’ll consider becoming a member.

Today, I want to follow the advice of my friend Anil Dash and make a long thread into a blog post.

Over five years ago, I began writing about a problematic trope in politics and media that’s continued to trouble me: the misleading notion that what we say and do online isn’t real.

That might seem to go against the grain of the current zeitgeist, where synthetic media generated by artificial intelligence, false news, and bots on social media are making headlines, but bear with me.

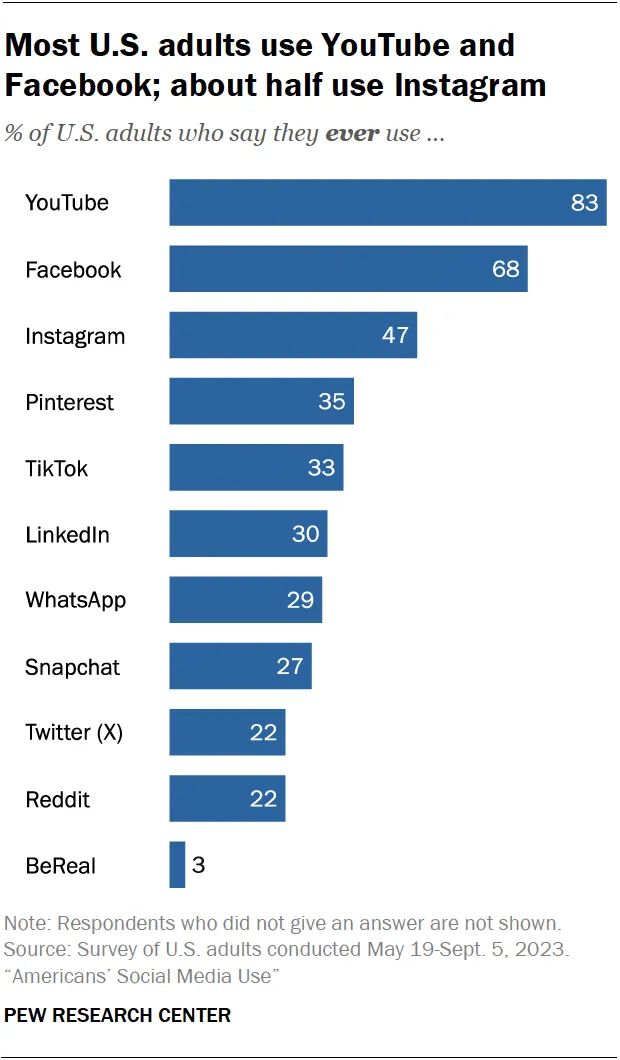

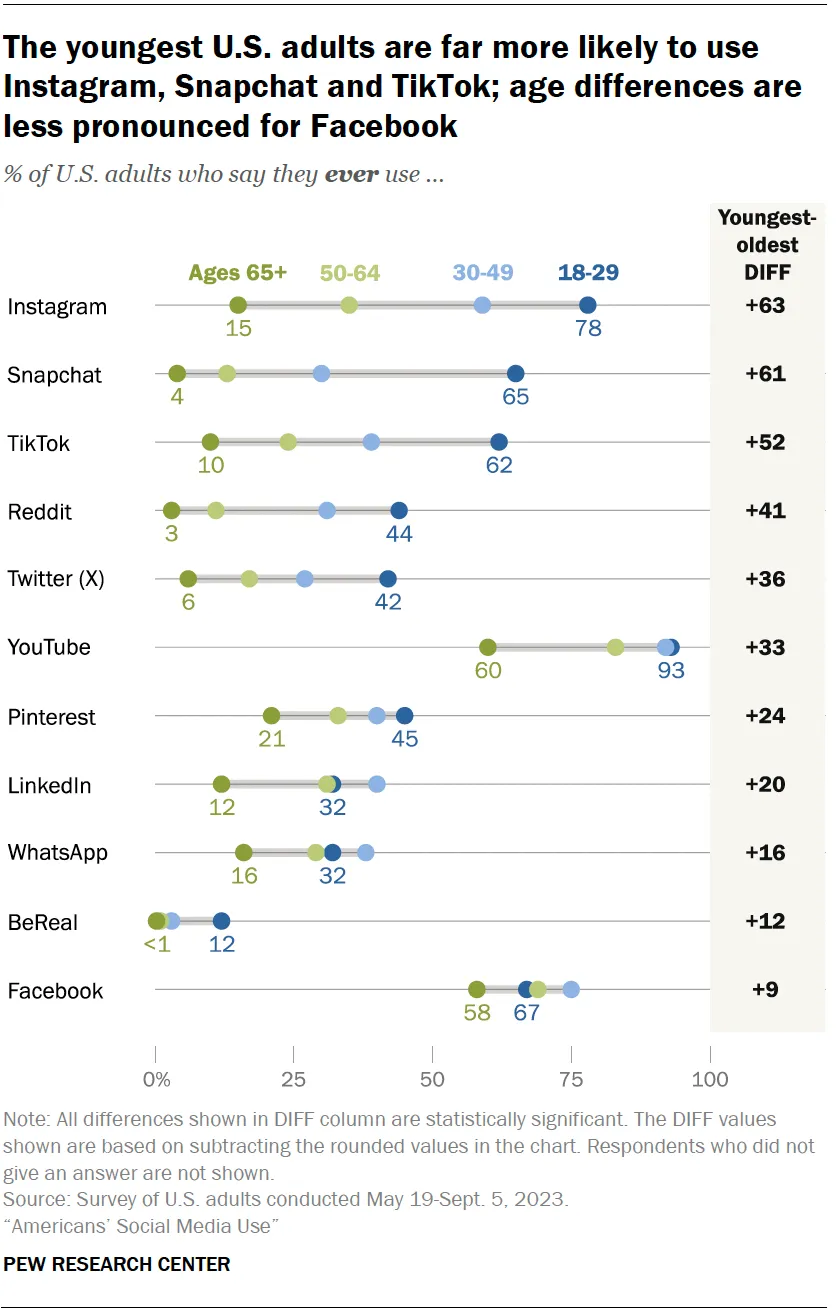

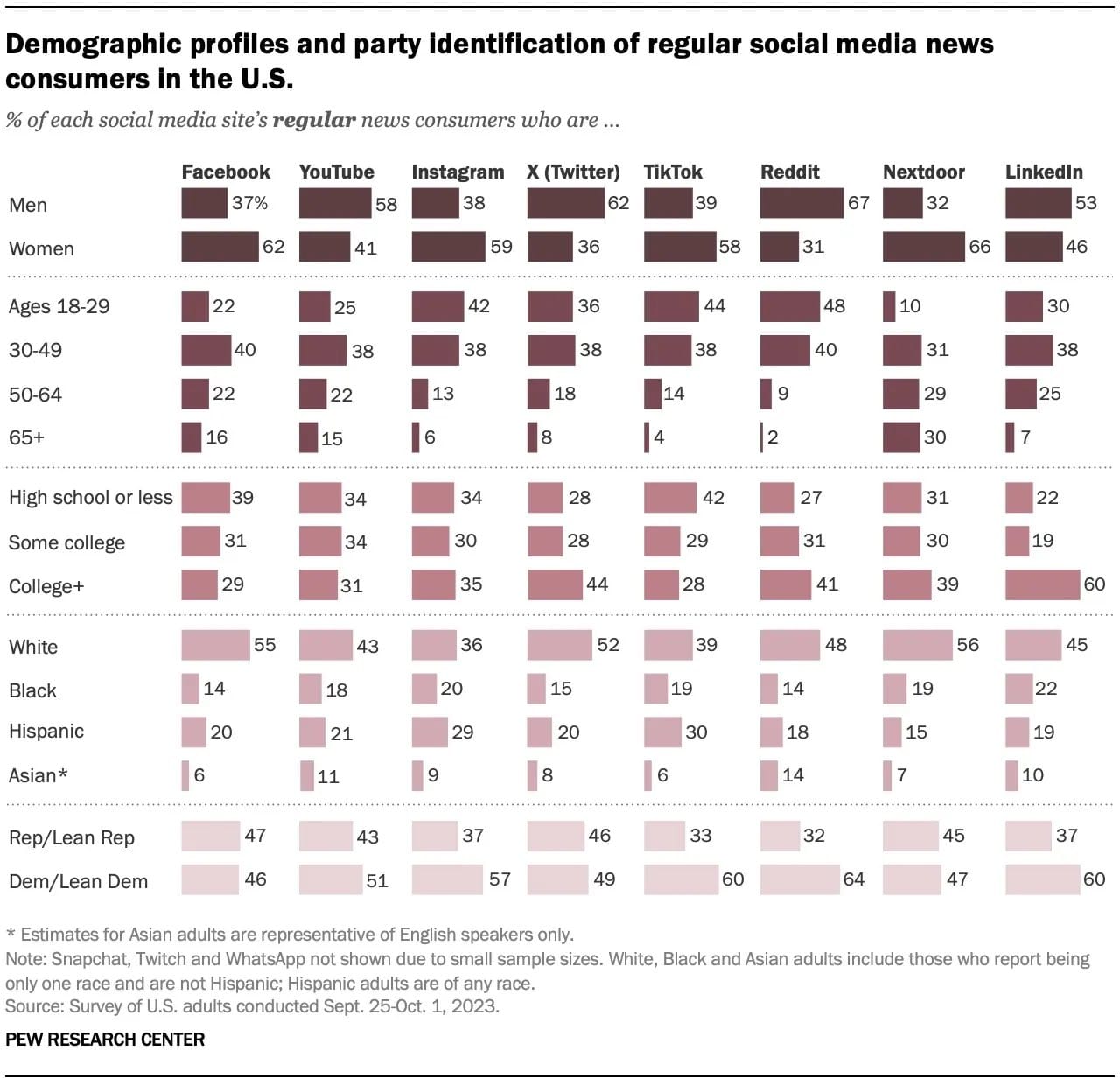

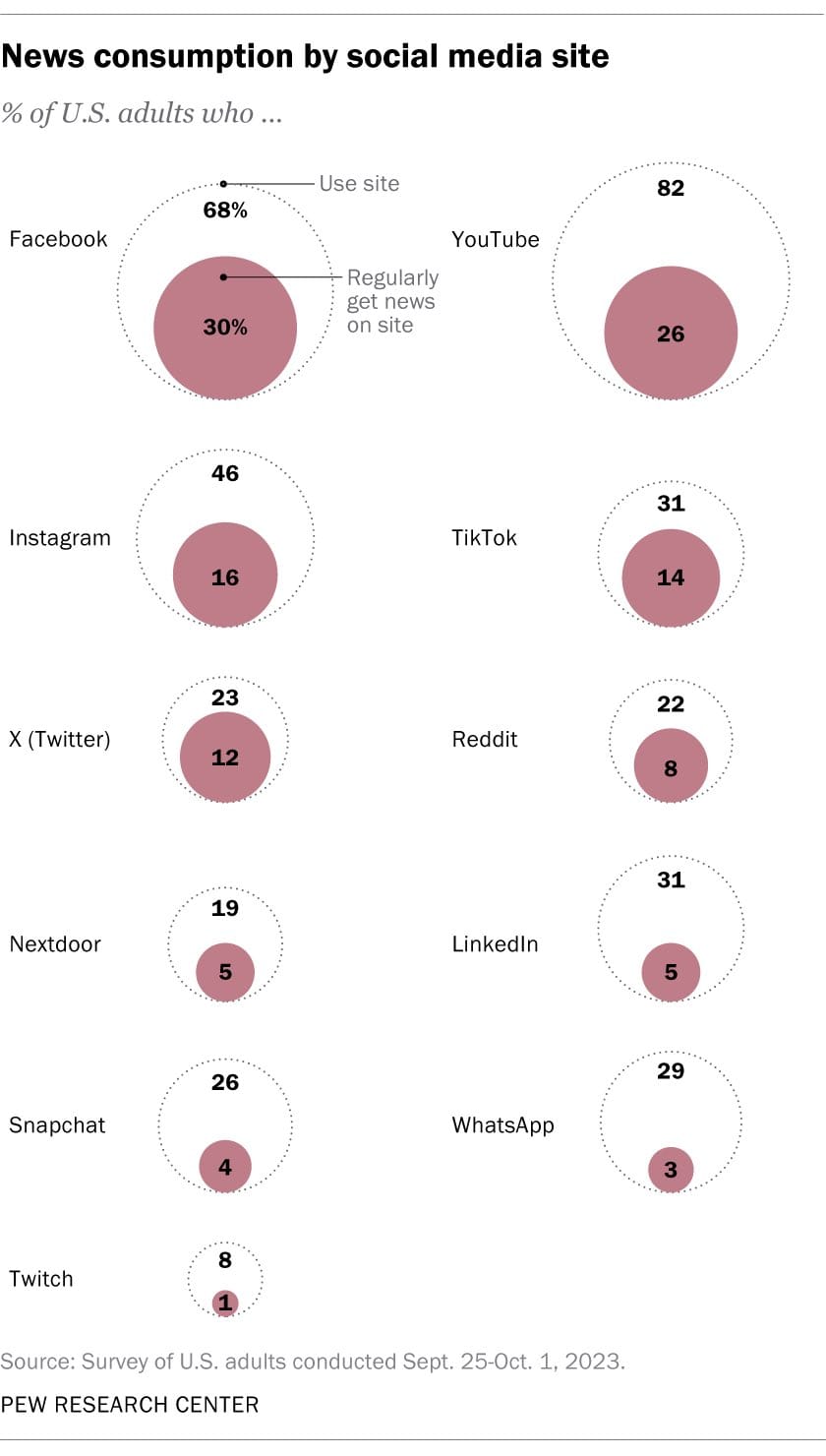

It is accurate to say that the demographics of the people who use online platforms are not representative of offline communities, as the Pew Research Center’s Internet and Life most recent survey of the social media American adults found in January 2024.

It is inaccurate for media, politicians, and officials to claim that is “Twitter isn’t real life.” If you want to get a sense of how widespread this is, listen to the montage in this 2022 episode of “On the Media.”

This signals to the public that social media isn’t real. It’s a mistake. It’s far better to say offline.

I‘m far from the first person to make this point, but it bears repeating. Back in 2013, Chris Suellentrop called this out clearly:

The habit of insisting that the virtual life is somehow not part of real life has diminished with time. Few people regard, say, online magazines as fake magazines anymore. And more than one politician has been felled by a scandal involving sex that was purely digital. So even though it wasn’t physical, it must have been real. Right?

As he observed, online activities “aren’t imitations of reality. They aren’t less versions of what goes on in the real world. They are the real world.”

But that hasn’t stopped folks from continuing to say that “Twitter isn’t real life” in the decade since.

In the interim, how and where adults access and use the Internet, the Web, social media & apps has dramatically changed with the rapid adoption of smartphones & rollout of mobile broadband. This shift is happening globally.

Over that time, we have also been reminded again and again that what we doonline matters offline:

If you are still casual in what you like, share, or post online in 2024, remember it’s all public.

Any social media post can go global in an instant, shorn of context, weaponized against you or others.

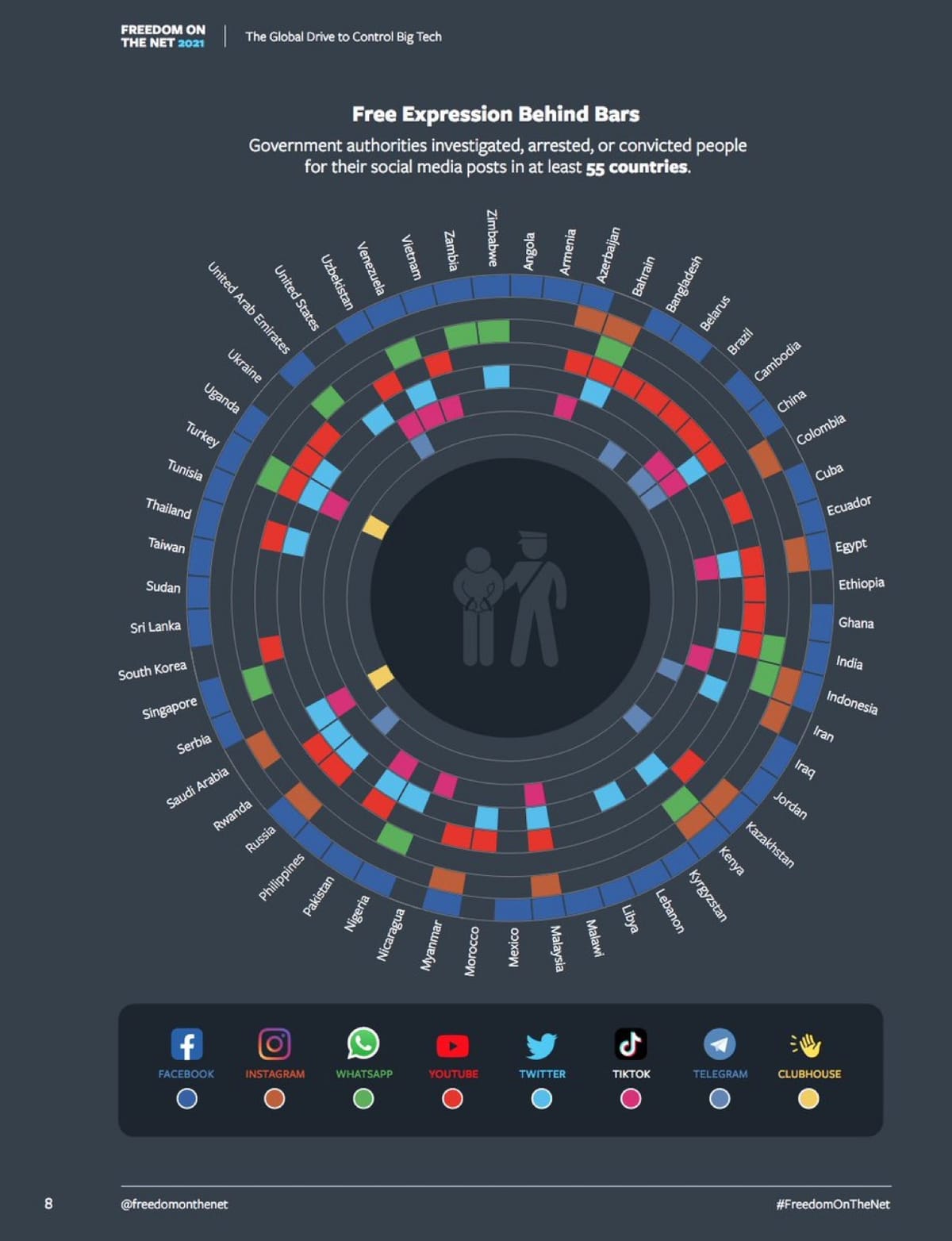

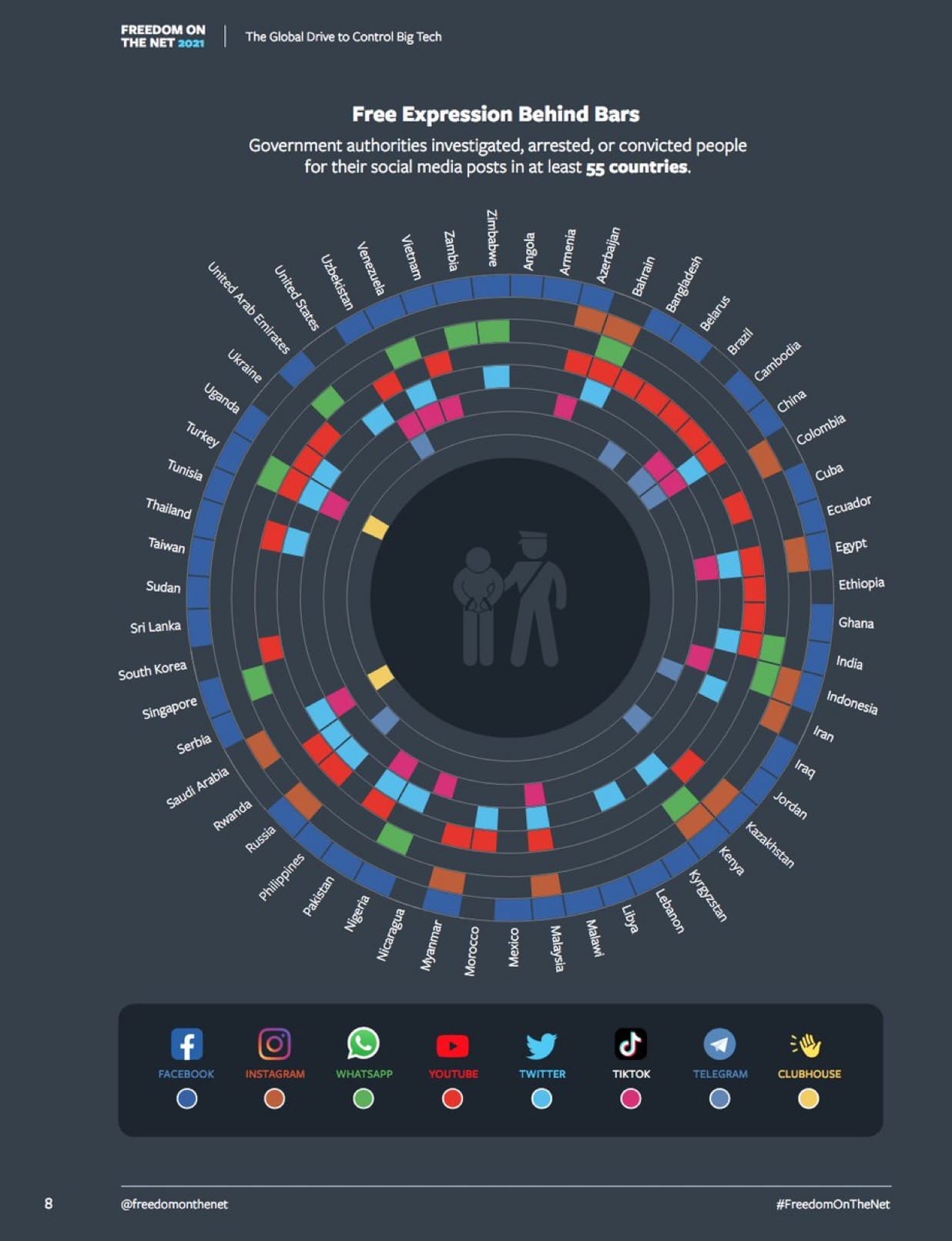

Tweet like every tweet might be read by your mom, shown on cable TV, put on a billboard, discussed in class, or published in the newspaper, held against you in a court of law, or brought up in your nomination hearing — because they could be. In 2021, Freedom House found government authorities have investigated, arrested or convicted people for social media posts in at least 55 countries.

Today, many more of us know that what happens online doesn’t stay online. It never did. Unfortunately, the impact of this trope hasn’t just led folks to be too careless or unwise about what they post.

Around the world, many police officers, editors, and politicians still don’t take networked harassment and abuse seriously — nor the threat of offline violence.

That culminated in the most serious national security failure at the U.S. Capitol since 1814 on January 6th, 2021, when disinformed partisans who believed Trump's tweets assaulted federal police officers seeking to stop the transfer of power.

That infamous day was "a demonstration of the very real-world impact of echo chambers,” as Renee DiResta told the New York Times. The insurrection on January 6th was "a striking repudiation of the idea that there is an online and an offline world and that what is said online is in some way kept online.”

“The insurrection is the latest and, in some ways, the most alarming lesson in how online extremism can translate into offline violence, but it should be the least surprising,” wrote Kaitlyn Tiffany, in the Atlantic. “It was building in online spaces…before the election, &…escalating ever since.”

And yet, the toxic trope that “Twitter isn’t real life” not only endured in the Biden White House, but festered across the news media outlets that inform and shape elite opinion and policy.

“Twitter isn’t real life (as top Biden adviser MIKE DONILON, who isn’t on Twitter, has pointed out) and you shouldn’t read too much into who follows whom,” reported Politico, in an article on who 90 WhiteHouse official accounts followed.

Donilon was wrong. Twitter isn't representative of offline populations. It wasn't designed for healthy conversations.

It has fake accounts and bots.

But what officials say or what they don't matters. Who they listen to matters. So does who they block, or ignore. That’s one reason why Elon Musk bought it at what seemed to many folks like an inflated valuation.

Commenting on Musk’s purchase in 2022, Ezra Klein both reified the trope and accurately described the offline influence of the online platform: “It’s become cliché to say Twitter is not real life, and that’s true enough. But it shapes real life by shaping the perceptions of those exposed to it."

Ben Smith, to his credit, acknowledged to the New Yorker in late 2022 that “lots of things have happened on Twitter that are really important” and that “Twitter’s a real part of the world, I would think.”

While leaders and scholars like Karen Kornbluh and Ellen Goodman made a thoughtful proposal in the wake of January 6th to “treat America‘s debilitating information disorder” by clarifying that “what happens online is subject to the same legal standards as what happens” offline, they still used the “real world” frame.

The digital dualism didn’t end, despite the irrefutable evidence that Trump’s tweets were quite “real” to those he targeted and abused, or to the partisans who believed his lies about widespread election fraud.

Media reporters like Brian Stelter who should have known better by February 2021 kept it going, even while he defended female journalists who were targeted with misogyny and hatred online.

Racist, sexist abuse directed at @seungminkim & female journalists online is real: https://t.co/c9unzRCgML

— Alex Howard (@digiphile) February 28, 2021

So was @whcos retweeting defense, showing support for press. @BrianStelter said it was “important” (I agree), but then “Twitter isn’t real life.”

Can’t have it both ways. pic.twitter.com/Byi1GPrH6z

That shouldn’t be surprising. For decades, the cable news networks and newspapers Stelter watched, read, and covered had spread the notion that what happens online isn’t “real,” while putting liars who spread “alternative facts” on air.

There is no doubt that Twitter is not representative of offline populations, and folks who tweet often are even less representative, but if someone makes a claim that “Twitter isn't real life” in 2024, ethical reporters shouldn't quote the clichéd falsehood without challenging it – even a “senior White House official.”

Even if January 6th didn’t put the trope in the coffin, the historic pandemic that brought millions of people online to work, learn, teach, and connect should have dragged and dropped this frame in the trash can.

Of course, it didn’t.

In August 2021, even Extremely Online reporters like Taylor Lorenz wrote that “the No More Lonely Friends gatherings are the latest example of online interactions turning into real life events in the pandemic."

Punchbowl News, a new, entirely digital outlet that reports on Capitol Hill, kept it going.

And they really mean it.

Axios, another born-digital outlet, uses the trope in promoting conversations about how online misinformation influences offline harms, like vaccine hostility.

The Intercept, which is also a digitally native outlet, made a more nuanced approach in its reporting on progressive nonprofits: ”Twitter may not be real life, but Slack is.”

Well, yes. In a world of remote work, Zoom, Slack, Twitter, email, and Google docs are all very much a part of real life, and folks & organizations who forget that will keep learning and relearning that truth to their sorrow.

Semafor, another new media outlet born digital, still doesn’t get it in 2024 — despite co-founder Ben Smith‘s influence.

There are signs that more and more people now understand.

Nobel Laureate Maria Ressa, one of my heroes, argued in 2022 that “we need the checks and balances we have to extend to the digital world. There is only one world, and to pretend like the virtual world is something different is just a way for companies to continue making bucketloads of money at our expense."

Ukrainian President Vladimir told Wired in 2022 that “people study online, get information; people read, people use it "The Internet is a reality. It is not another world, but rather a modern reality."

Conspiracy theorists are intimidating voters, politicians, election officials, and public health workers online and offline — both of which are quite real to the people on the end of the threats, implied or otherwise. People who believed lies acted violently on January 6th. It’s going to keep happening, as white supremacists connect and organize online.

In 2024, data from Pew Internet shows that the demographics of many online platforms are still not representative of offline populations — especially rural, poor, or elderly — but not that the “Internet is not real life.”

Our friends are online.

So are our families.

That’s why social media posts reach real people.

It’s why campaigns court “influencers” & “self-important podcasters.”

The sooner politicians, pundits, and press drop the toxic “Internet is not real life” trope, the sooner we can have deeper, more serious conversations about when, where, & how our participation and actions online affect what we experience offline, from elections to education to collective facts about climate change or public health.

What happens online is real.

Networked abuse is real.

Censorship is real.

Purchases and sales are real.

Statements & orders from officials & politicians to shut down apps or censor websites are real.

Remote work is real.

Access to life-saving information and services are real.

“Twitter could have been, should have been, so much better,” observed historian Thomas Zimmer, ”but casually dismissing the platform as ’not real life’ has always been silly – its enormous influence on the broader public, media, and political discourses is undeniable.”

Get smart: What happens online matters offline. Stop using the “real world” frame.

As always, thank you for supporting this work, subscribing, reading, and sharing with real people in your networks and communities. You can find me at alex@governing.digital with comments, questions, tips, or other feedback.