2024 showed us why presidential debates remain essential democratic institutions in the USA

Good afternoon from Washington, where I‘m experiencing the trials and tribulations of being a member of the ”sandwich generation.” As always, thank you for subscribing and amplifying Civic Texts, which will not be sustainable without your support.

On a personal note, it has been deeply heartening to have many more of you listening after the publication of my essay in the New York Times on Tuesday. To everyone who has been able to support my work and subscribed to memberships: Thank you so much. It means a great deal to me and my family this week as we cope with new health challenges. -ABH

Last night’s debate offered a novel study in contrasts between Republican Presidents.

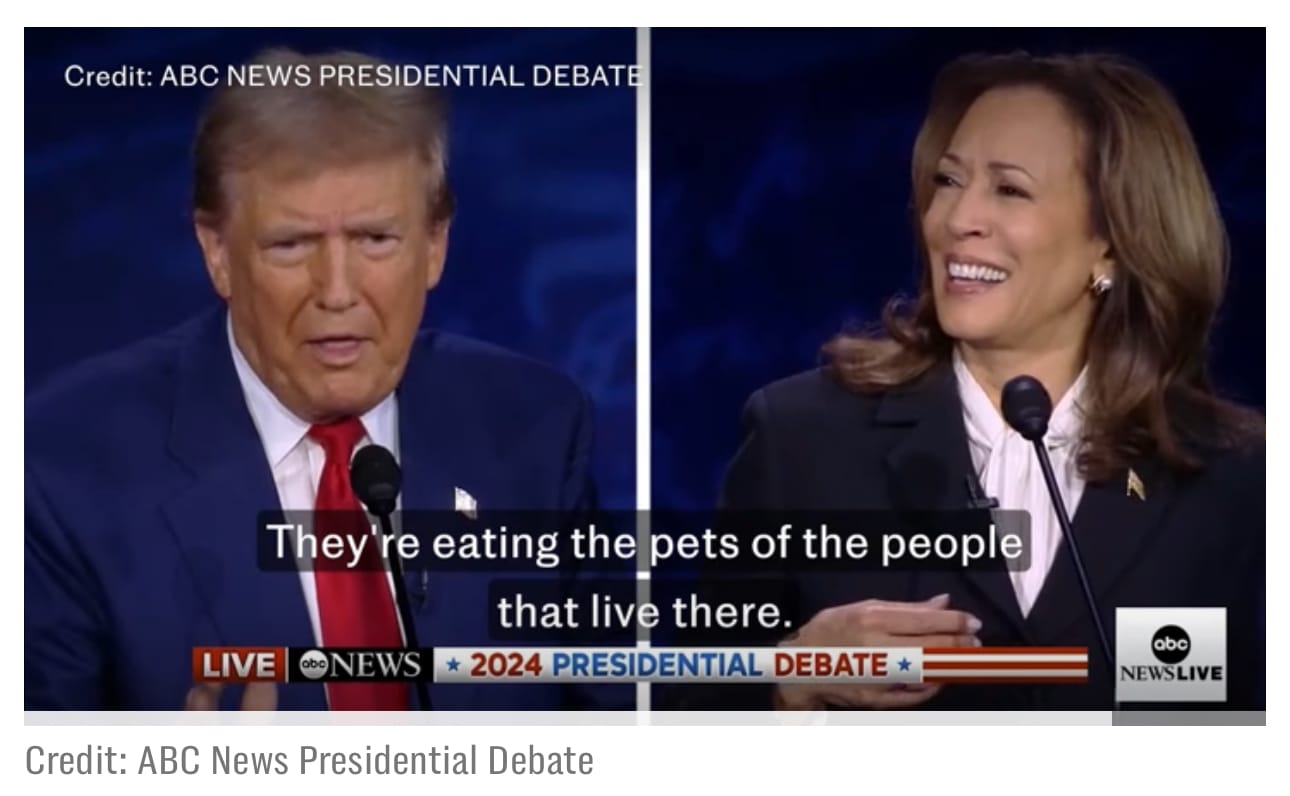

1 score and 15 hours ago, Donald Trump falsely claimed that in Springfield, Ohio “they’re eating the dogs. The people that came in — they’re eating the cats. They’re eating the pets of the people that live there.”

Trump, a twice-impeached businessman, reality TV star, and convicted felon repeatedly indicted for conspiring to defraud the United States and retaining top secret government records, is seeking to win re-election to evade accountability by blatantly fear-mongering about immigrants.

8 score and 6 years ago, Abraham Lincoln said in Springfield, Ohio that “a house divided against itself, cannot stand. “I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave & half free.”

Lincoln, who at the time was a lawyer seeking to win election as a U.S. Senator, would go on to hold a series of debates with Senator Stephen A. Douglas on the past, present, and future of slavery in the United States that would capture the attention and hold the interest of Americans across a sprawling union.

That outcome was the direct result of new technologies of the mid-19th century that were applied towards civic purpose. Members of press and stenographers transported by railroad to capture the words in shorthand, and a telegraph to transmit those transcripts nation-wide.

While the Lincoln-Douglass debates are often held up to history students as the pinnacles of politicians using rhetoric and reason to explain and parse issues of profound national importance, close examination of the complex, hour-long legal arguments the candidates levied over the seven occasions shows “pandering, baseless accusation, outright racism and what we now call ‘spin’,” as Fergus Bordewich observed in Smithsonian Magazine in 2008.

As the French might say, albeit more elegantly, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Over a century later, Americans may reasonably question how well televised debates still serve a civic purpose in our bitterly divided nation.

Do they provide us with an explanations of what ails us as a nation or how our government of the people would respond under the leadership of a candidate, or just how well they can debate on camera?

A succession of technologies has radically changed access and distribution, from radio to broadcast television to cable TV to the Internet, streaming video, social media, and smartphones.

Candidates now consider not just how to generate made for TV moments, but lines and expressions that may go viral, aided by press seeking fresh angles or partisans and campaigns spinning in real-time.

While candidates, questions, moderators, format, and context of presidential debates have all changed over the decades, however, this year showed us why these quadrennial public forums still remain an essential institution in American democracy.

In fact, the two presidential debates profoundly mattered in 2024 — perhaps more so than any in American history.

Unlike so many of the previous presidential debates that have helped Americans measure the presidential timber of whichever nominees our major political parties had elevated for consideration in an election years, each of these forums has had a singular impact on our history and the future of our union.

In June and September, Americans have had signal opportunities to assess the fitness of a current and a former president to stand for re-election because of a profoundly American tradition that is neither mentioned nor codified in our Constitution.

In the wake of one of the worst debate performances in modern American history, President Biden announced he would not seek re-election after all, endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris, finally passing the torch to the next generation of leaders after half a century of public service.

Last night, former President Trump turned in a historically poor performance, laid low not simply by the onset of age or travel in a late hour, but by the glaring deficiencies in his character and temperament that make him unfit for public service, much less the presidency.

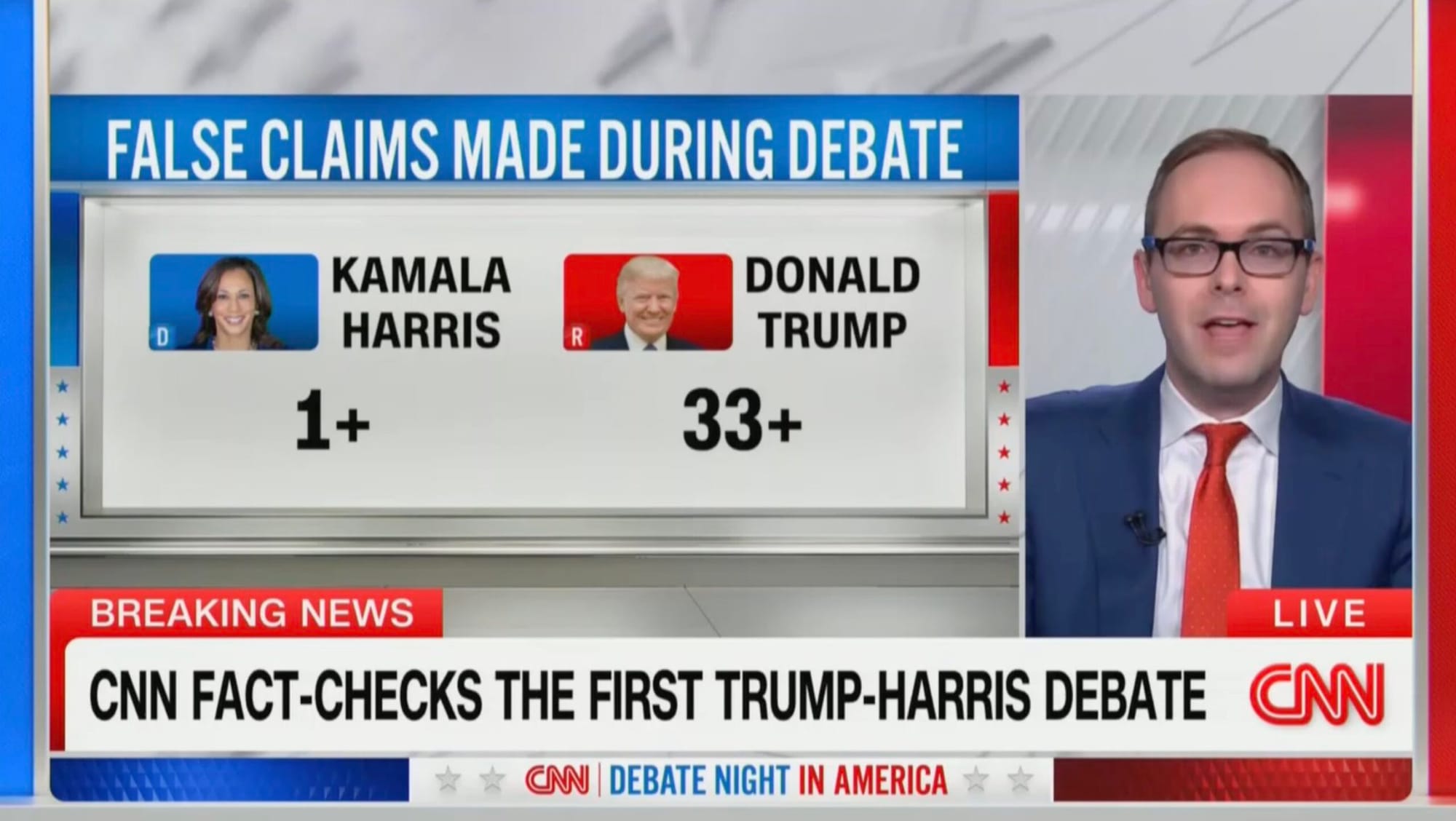

Trump showed us who he is, repeating an online rumor about immigrants with a long, ugly past, then angrily doubling down on it when a journalist moderating the debate calmly and clearly corrected him in the moment. Trump repeated amother debunked lie about doctors killing babies after they are born, and was again fact-checked on air.

While Trump and his partisans have angrily attacked the journalists who moderated the debate for fact-checking him, the fault lies with the candidate who is unable or unwilling to tell Americans the truth or amend his false claims when presented with evidence that debunks them.

With Trump, this is a feature, not a bug. He was the single biggest source of misinformation during the pandemic, after rising to the power on the back of a racist lie about the first Black president in American history.

Trump once again ran the autocrat’s playbook at the debate, denying, disinforming, and casting doubt on everything from government statistics to energy production to undocumented immigrants voting to the integrity of our elections.

It was no accident that Trump cited Victor Orbán of Hungary as an example of a world leader he admires, given how effectively Orban has institutionalized illiberalism in that nation.

To get a sense of what autocratization looks like in transition, read Andrew Higgins’ dispatch from Bratislava about Prime Minister Robert Fico, who has “presided over a rolling purge of anticorruption prosecutors, museum and theater directors, journalists and others he holds responsible for an atmosphere of “hatred and aggression” that he says led to the attack.”

While Harris’s statements weren’t free of misstatement, understatement, or omissions of fact, you can see how the fact-checkers at the Washington Post had to parse the details to find significant fault with her claims.

In contrast, Trump’s habitual fabulism remained detached from reality, making wildly inaccurate, ahistorical claims about inflation to “whataboutism” in response to questions about the failed putsch he incited on January 6th, 2021, after his attempted auto-coup had failed.

Instead of expressing regret about his role in the worst act of national security reach at the Capitol since 1814 or the dozens of police officers who were injured after being assaulted by his partisans — much less the conspiracy to defraud the United States that preceded it — Trump doubled down on debunked lies.

The failure of the moderators to effectively question him about the details of the federal or state indictments — or ask why he’s dangling pardons militia members convicted of seditious conspiracy or assaulting police or terrorizing Members of Congress not to verify votes — doesn’t reflect particularly well on ABC News, but that’s a separate matter from what the debates show Americans and the world.

The fact that presidential debates mattered so much in 2024 should not distract from the atrophy we can see an 19th century institution expected in prairie politics into a 21st century world.

The evolutionary changes that Trump’s behavior provoked should be followed by revolutionary changes in format that bring Americans more into the conversation and ensure that our greatest concerns are reflected in the topics the candidates engage.

The format and rules debates were negotiated between the campaigns, and it showed in the questions.

The absence of several significant public policy issues related to technology and good governance from this debate was noticeable to me — and to others, like journalism professor Nik Usher, who posted on LinkedIn about the void:

“We did not hear anything about generative AI. At all.

We did not hear anything about tech platforms or big tech.

We didn’t hear anything about freedom of expression - either online/digital platforms or in reference to book bans.

We did not hear about Musk or any big tech ubermensch.

We only heard about innovation in reference to small business loans. Tech manufacturing was barely discussed other than chips, and briefly as part of a different convo on trade.

We did not hear any discussion of disinformation or misinformation or influence operations. Trump has taken to using disinformation as a way to discredit fact-based journalism (that’s just disinformation) giving the term a new valence just as he did with fake news.

We did not hear anything about local news or tech and media policy. I personally think either Harris or Trump, in their own ways, could talk about rebuilding news media to strengthen American communities.”

17 years after a snowman on YouTube asked a question about climate change, we’ve seen atrophy and steady withdrawal from the potential of emerging technologies to strengthen our democracy in the United States, instead of a fundamental reinvention of the debate format or function that challenges candidates to explain how they’d respond to a pandemic, war, natural disaster, or alien invasion.

Back in 2010, the Personal Democracy Forum relaunched 10Questions.com to try to reboot citizen-to-candidate engagement.

14 years later, there’s no sign of campaigns or newsmedia networks enabling citizens “to submit videos of questions for candidates, vote on the best and then rate the quality of the answers” in partnership with social media companies or nonporift civic technology organizations.

There’s not much reason to be optimistic about Trump or Harris proposing or agreeing to a more participatory forum this year. As of today, it’s not even clear if there will be a second debate at all — Trump said he won’t — though it’s plausible he might accept one on Fox News with partisan moderators.

But it would be to the benefit of the American people if every candidate for state, local, or national office did so, with care and intentional design, demonstrating an interest to be accountable to all constituents, not just those who cast a ballot for them.

As I’ve said before, regular press conferences, town halls, and structured online dialogue make candidates and presidencies stronger over time.

Transparency, honesty, accountability, and participation over time are not just the way back from historic lows in trust, but a way forward to rebuilding the broken relationship between elected officials and the publics they serve.